How did MLK Jr. Become a Socialist?

A forgotten network of radicals helped teach King how to organize—and how to link civil rights to economic redistribution for all

Almost everyone left of center now understands that Martin Luther King Jr. was more radical than the milquetoast, “I Have a Dream”-only version many Americans grew up with.

MLK Jr. was a political radical who spent his final years opposing militarism, denouncing capitalism, and demanding a massive economic redistribution. That’s why Zohran Mamdani’s go-to definition of socialism has been to quote King: “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

And yet, even many of the most sympathetic “radical King” accounts still cling to a familiar American fairy tale: the Great Man who simply had it in him—born with moral courage, hatched fully formed, and then leading history forward by sheer force of charisma.

That story is wrong in a specific way that matters for today’s left. King’s radicalism wasn’t a private attribute. It was the outcome of apprenticeship inside an organized tradition—a network of socialists, labor radicals, and movement educators who did the unglamorous work of training leaders, building institutions, writing drafts, running logistics, teaching strategy, and connecting civil rights demands to bread-and-butter class politics.

It’s unfortunate that this institutional legacy has been scrubbed out so successfully that people might end up thinking King invented his own politics in isolation. In reality, he came up inside a web of socialist organizers and “movement schools” that treated racial justice and economic justice as inseparable—and, crucially, treated organizing as a craft you could teach.

Part of what makes the erasure so effective is an accompanying myth: that early American socialists—especially those associated with the old Socialist Party—“ignored race,” full stop, and therefore couldn’t possibly have helped seed the Black freedom struggle’s mass politics. There’s a kernel of truth there (the history includes shameful racism and exclusion), but it’s also a caricature that turns a complex tradition into a straw man—and, conveniently, makes it easier to pretend that socialism and antiracism only meet in the 1960s as a kind of happy accident. In reality, the US Socialist movement—including former racists like Victor Berger— after 1917 forcefully attacked white supremacy and empire rather than accommodating them, establishing an organized legacy that went on to play a central role in MLK Jr.’s politics.

This isn’t an argument for diminishing King’s heroism or agency. King was extraordinary. But if we care about the kind of politics he practiced—mass organization, movement discipline, and democratic socialism—we have to pay attention to the scaffolding that made it possible.

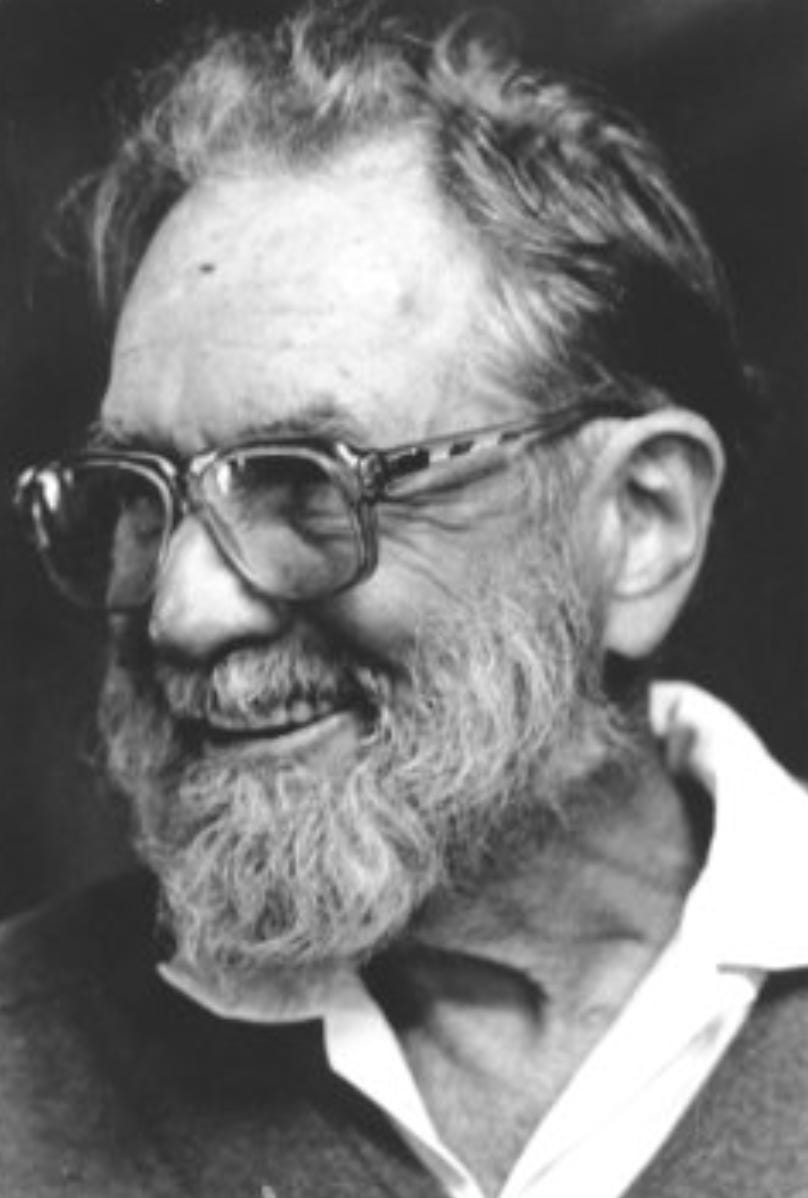

Myles Horton and The Highlander School

It’s tempting to treat the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott as the instant birth of the modern civil rights movement—one brave woman refuses to stand, a young pastor gives a speech, history turns. But the boycott succeeded because it sat on top of years of organizing: NAACP networks, church infrastructure, labor-style discipline, and political education.

Rosa Parks is often flattened into a symbol—quiet seamstress, tired feet, spontaneous defiance. But Parks was a serious organizer, a student of movement strategy, and someone who had been steeped in the traditions of interracial radicalism and labor solidarity. Her decision to sit in the front of the bus in December 1955 didn’t come from nowhere. It came from training, relationships, and political formation—including her relationship to one of the most important movement institutions of the twentieth century: the Highlander Folk School.

Highlander, based in Tennessee, was a radical training ground born out of the labor left of the 1930s. Its founder, socialist Myles Horton, saw it as a place to build power from below—first in the labor movement, and later in the southern freedom struggle.

Myles Horton came out of a world where socialism was a practical current in working-class life. Horton had studied under Christian socialist Reinhold Niebuhr and in his autobiography he describes learning politics from people like “the old Socialist, Joe Kelley Stockton,” a friend of Eugene Debs who made socialism tangible through his generous daily life and fierce class struggle politics.

Highlander, launched with financial support from Niebuhr and the Socialist Party, wasn’t designed to produce charismatic leaders, but to produce collective capacity—to teach ordinary people to analyze their conditions, talk to each other across divisions, and act together.

As Horton put it, Highlander existed so people didn’t wait for “some government edict or some Messiah” to improve their lives. Its radically democratic pedagogy insisted that “the best teachers of poor and working people are the people themselves,” and that the point was not adjustment to an unjust society but its transformation.

And though it often gets forgotten today, Highlander’s early political DNA was explicitly socialist. In one fundraising appeal, Horton described Highlander’s goal as “education for a socialistic society” and he made clear the school’s commitments: it existed “to help create a new social order.”

The school’s early focus was heavily labor-oriented—mostly white textile and mine workers in the mountains—but Horton and his team moved toward racial justice as they confronted the South’s core system of rule. Horton reached out to Black labor organizers in the 1940s and by the 1950s shifted Highlander’s focus “completely” toward fighting segregation.

Rosa Parks and Montgomery

Rosa Parks’s relationship to Highlander is one of those threads that gets cut out of the story because it complicates the heroic myth. Parks didn’t just feel her way into resistance. She prepared.

Montgomery’s movement anchor, Black labor organizer E. D. Nixon, insisted that effective civil disobedience required “careful planning” and “a well-trained and disciplined core of leadership.” This was the logic he had been taught at Highlander: organization first, then disruption. Thus Nixon arranged for Parks and other local Black activists to attend the school in August 1955 for a two-week intensive multi-racial training. Parks later recalled:

At Highlander, I found out for the first time in my adult life that this could be a unified society, that there was such a thing as people of different races and backgrounds meeting together in workshops, and living together in peace and harmony. It was a place I was very reluctant to leave. I gained there the strength to persevere in my work for freedom, not just for blacks, but for all oppressed people.

Montgomery’s subsequent boycott matters here not only because it propelled that as-then-still-unknown King into national leadership, but because it was the first major breakthrough of the modern civil rights movement’s mass-action model: sustained collective discipline, economic pressure, and moral confrontation with Jim Crow power. It turned the struggle from courtroom battles into a social insurgency. King’s gifts—his voice, his steadiness under pressure, his ability to frame the fight in moral and democratic terms—were real. But the movement around him was also teaching him what kind of leader he needed to be.

That teaching came from people who already knew how to organize. And a surprising number of those people came out of socialist and labor traditions.

Bayard Rustin

If you want to point to a single figure who helped turn King from a gifted local leader into the organizer of a national movement, Bayard Rustin is hard to beat. Rustin treated nonviolent mass organizing as a technology of power. It was something you trained for, drilled, organized, and executed with precision.

Rustin is sometimes remembered as the man behind the 1963 March on Washington. That’s true—but it sells him short. Rustin wasn’t just an event planner. He was a strategist who carried decades of political experience in labor coalition-building, in Gandhian nonviolence, and in building structure and discipline. He was also a committed democratic socialist. As he put it in a 1958 report on his recent trip abroad, “The problem in Europe—as in the United States—is the absence of a vital socialist movement.”

Rustin also helped shape the intellectual and strategic framing of Montgomery. He constantly pushed King and other leaders to think bigger: don’t treat the boycott as a local dispute; treat it as a model. Don’t treat segregation as a “Southern problem”; treat it as a national crisis of democracy. And don’t separate civil rights from economic rights.

That last point is crucial. Rustin’s politics came out of a socialist tradition that understood racism as inseparable from political economy. He was relentless about moving from protest to power via majoritarian working-class politics.

This is also where Rustin’s own life shaped his political commitments. He lived as an openly gay man in a movement world that was often hostile to homosexuality. He survived repression, marginalization, and surveillance. Those experiences sharpened his sense that moral purity is not enough. You need organization strong enough to win.

King absorbed a lot of this. The “King style” people now admire—moral clarity fused with disciplined organizing and broad coalition politics—didn’t come only from the pulpit.

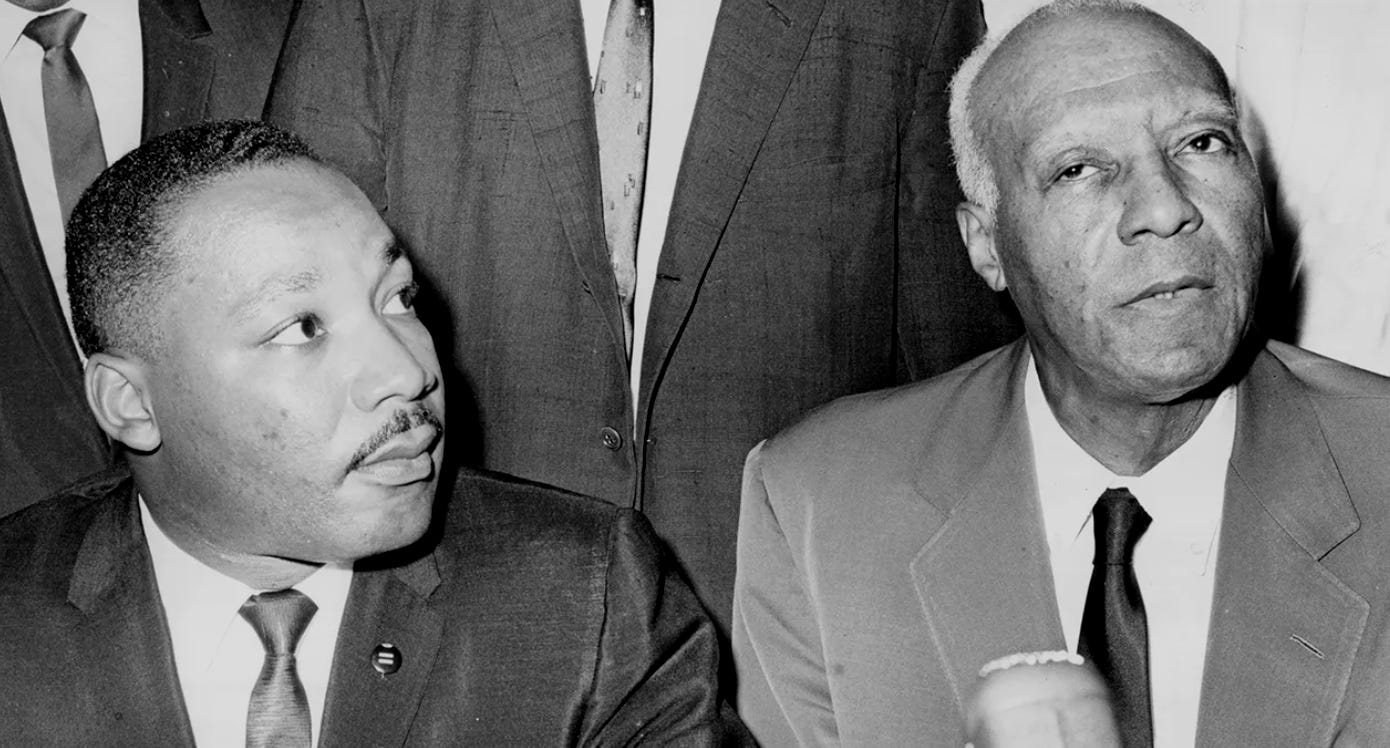

A. Philip Randolph

If Rustin helped professionalize strategy, A. Philip Randolph helped define the movement’s relationship to labor and economic justice.

Randolph became a Socialist Party leader in a Harlem milieu that fused class struggle with a Black freedom politics. In New York he and his co-thinker Chandler Owen tried organizing unions, got fired for telling the truth about low wages, and, with backing from the left-wing Jewish Daily Forward, launched The Messenger in 1917, which they advertised as “The Only Radical Negro Magazine in America.”

Randolph’s socialism was a way of reading power and a way of building it. He believed Black freedom couldn’t be won only through courtroom victories or moral persuasion, because segregation was anchored in material domination: jobs controlled by bosses, housing controlled by landlords, and politics controlled by those who owned the economy. That conviction pushed him toward the hardest terrain in American life — Black labor struggles — and the belief that democracy required economic power for working people.

Randolph’s Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters wasn’t simply a successful union—founded in 1925 to organize the thousands of Black men working as Pullman porters on the railroads, it was the first major Black-led union to win a charter from the American Federation of Labor. It became a training ground for a generation of Black working-class organizers—including E. D. Nixon in Montgomery—who understood how to pressure institutions, bargain collectively, and build durable organizations.

Randolph also pioneered a tactic that would define the civil rights era: the threat of mass action as leverage. His proposed March on Washington in 1941—aimed at forcing federal action against discrimination in defense industries—was a model of using mobilization to extract concessions. It showed that you didn’t have to wait for goodwill. You could force change.

By 1963, that Randolph tradition culminated in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, an event that is often sanitized into a warm memory of one speech about a dream. But the march’s very framing was a statement: jobs and freedom. Not just rights on paper, but economic demands.

And Randolph’s language was militant in its insistence on pressing forward. Randolph declared, “This march will not be stopped. It will go on.” That line was a warning to the political establishment that the movement would escalate until its demands were met.

Stanley Levison

Stanley Levison might be the least known of King’s key socialist advisers, but his impact was no less significant. Levison—introduced to King by Bayard Rustin during the Montgomery bus boycott—was a wealthy Jewish businessman and lawyer with a deep Marxist past, someone the government treated as a dangerous contaminant. Indeed, he was “a dyed-in-the-wool leftist” and “a full-blooded Marxist” until he severed formal ties with the Communist Party in 1956.

As his biographer notes, Levison did much of the backend work that made King’s work possible. Levison “counseled, raised funds for, ghostwrote articles and speeches for, did the accounting of, and often bailed out King” from 1955 to 1968.

That doesn’t mean Levison “made” King. It means King operated inside a support system built by seasoned organizers and radical intellectuals—precisely the kind of system that Great Man stories erase.

Levison also shaped King’s message in important ways, especially around class. As King put it in his book on Montgomery, the labor movement “must concentrate its powerful forces on bringing economic emancipation to white and Negro by organizing them together in social equality.” Levison’s politics mattered here. He was a Marxist with real ties to labor radicalism, someone who saw economic structure as the key to racial hierarchy. And he helped King articulate that link in public language.

Levison also brought a kind of ethical discipline that helped shaped King’s choices. When King considered a profitable lecture tour, Levison snapped, “You can’t do that,” and when King asked why, Levison answered: “Because the kinds of people that you will be preaching to about nonviolence are too poor to pay for your lectures.” King quickly agreed. It’s a small detail, but it underscores how personal virtue emerged from political discipline—one rooted in socialist movement culture.

A Forgotten History

If this socialist tradition mattered so much, why is it so absent from popular memory?

One answer is repression. Levison, Rustin, and others were targeted by the FBI and by politicians who believed civil rights could be discredited by association with socialism. J. Edgar Hoover treated Levison as “Mr. X,” a Communist figure supposedly infiltrating King’s circle.

Another answer is American political culture. Many people find it comforting to believe change comes from exceptional individuals, not from organization. It reduces history to biography. It lets you admire King without asking what kind of collective apparatus is needed to produce more leaders like him and to win real change.

And then there is the myth about early socialists and race: the idea that socialism is inherently blind to racism, making it easy to treat socialist influence on King as irrelevant or accidental. There were real failures and compromises across the white socialist and labor left. But there were also profound contributions—Randolph and Rustin’s entire careers being one of the most obvious. And their politics came straight out of the Socialist Party, which had made a sharp anti-racist turn after World War I.

The point is that King’s movement was built inside a broader left ecosystem that treated racial justice and economic justice as inseparable. None of this reduces King to a puppet. The opposite is true. King’s greatness was not just that he had advisers. It was that he listened, learned, and evolved. Many leaders resist that kind of learning. King actively sought it.

He also chose, again and again, to accept the risks that came with these relationships. Staying close to Rustin and Levison—both targets of intense repression—was not safe. It wasn’t politically convenient. King did it because he recognized that movements need thinkers, strategists, and builders, not just preachers.

The story of King’s radicalism is not the story of a lone genius. It is the story of a gifted leader who joined a tradition—and helped bring its best instincts to national scale.

No Solitary Heroes

We live in a moment when Donald Trump has helped hurl the United States back toward some of its worst legacies of racism, exclusion, and oligarchy. In this environment, the right lesson from King is that moral clarity has to be fused with organization, mass leverage, and material demands.

King’s most dangerous idea was never simply that racism is wrong. It was that democracy requires redistribution—what he and his circle increasingly framed as a kind of democratic socialism in practice: building a society where working people have power, where rights are real because they are backed by economic security, and where the fight against racism is inseparable from a fight for a better life for all workers.

That vision did not emerge from King alone. It was shaped and sharpened by a broader socialist tradition—through figures like Bayard Rustin, A. Philip Randolph, Myles Horton, Rosa Parks, and Stanley Levison—who taught him how to organize, how to think structurally, and how to connect the struggle for dignity to the struggle for material freedom for all.

More

Organizations in Minnesota have called for a mass day of “no work, no school, no shopping” on January 23. Each of us, and all our organizations, should try to participate nationwide. It’s all hands on deck to protect our communities from ICE terror.

In NYC, students will be walking out on January 23. The UFT, NYC’s teachers union, has also committed to participating in the day of action. Students and unions nationwide should follow their lead.

The fight to tax the rich in NYC has taken on an increased urgency after it was announced that the city is facing an unexpectedly large budget shortfall due to Eric Adam’s mismanagement. We need your help to canvass and phonebank our fellow New Yorkers — sign up here.

Excellent piece, as always, Eric. I would add that through Rustin and to a lesser degree Randolph, there was a cadre of mostly young, some middle-aged socialists who supported MLK's work. Michael Harrington was part of that group. There is a chapter in Harrington's Fragment of the Century on that work, and although I can't put my finger on my copy of the Isserman bio of Harrington, I believe it is in there too. Paul LeBlanc's and Michael Yates' A Freedom Budget for All Americans has the best account of the young socialists around Rustin. For reason the opposite of Victor Berger (later, as opposed to earlier, politics), they tend to be overlooked.

Great piece! Jack O'Dell is another important figure connecting King to anti-capitalist and labor organizing traditions. https://www.amazon.com/ODell-File-Kindle-Single-ebook/dp/B00M75QW7G