Don't Cancel Sewer Socialism

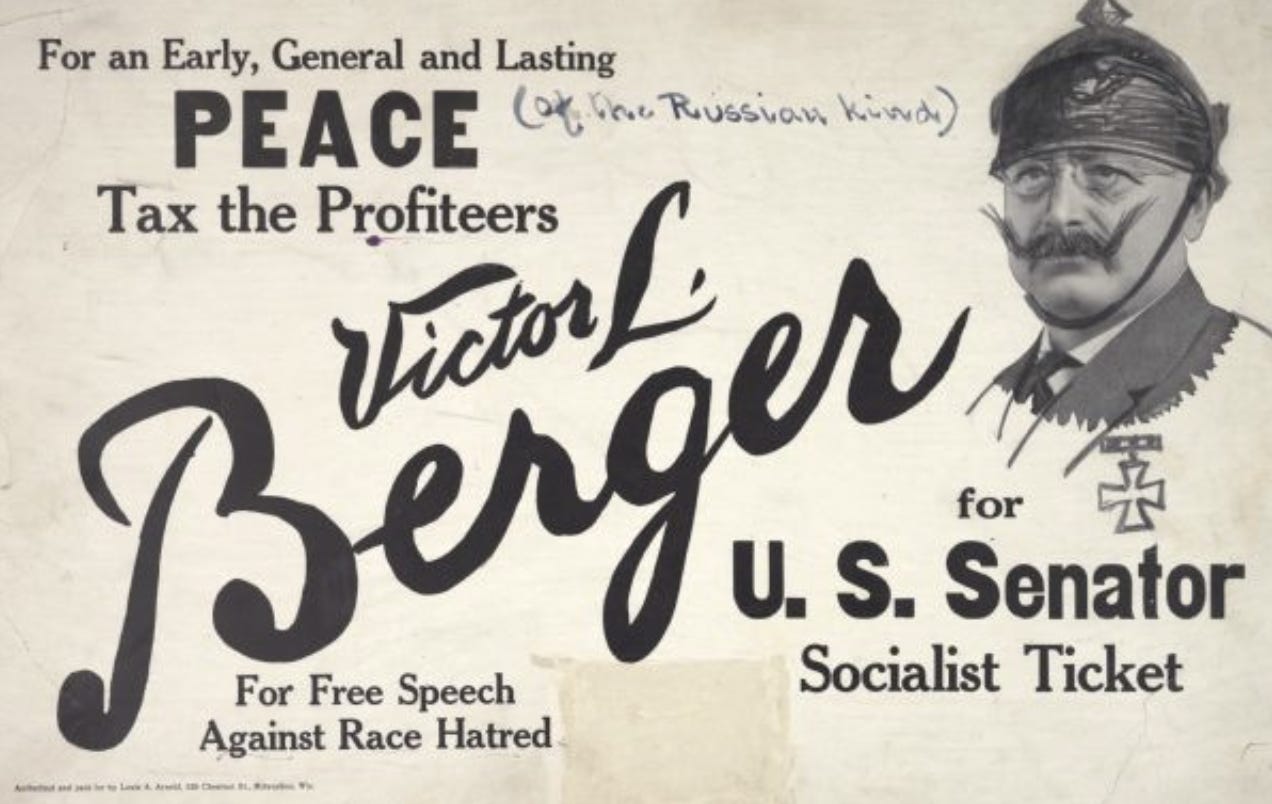

The unknown story of how Victor Berger went from peddling race “science” to fighting lynching—and why this matters now.

With an eye to the dilemmas and possibilities of having a socialist mayor in New York City, last month I published an article on the lessons of Wisconsin’s so-called sewer socialists, who governed Milwaukee for almost fifty years. It drew more readers than normal — as well as more blowback. To quote one critic, “Victor Berger was the godfather of the ‘sewer socialist’ movement and was also incredibly racist against Black people.”

Another polemical response insisted that white supremacist views were not a personal flaw of Berger. Rather, they arose from the sewer socialists’ “appeal to the lowest-common-denominator instincts of the workers whose votes they depended on, including racism.” Such criticisms echo a historiographic consensus, which for over 75 years has painted Berger as America’s prime example of a racist white socialist. Even otherwise sympathetic portrayals of Berger have suggested he remained a bigot his whole life.

Before I started researching Milwaukee’s socialists, I assumed that the consensus view was accurate. And that’s why I was so surprised to stumble across a 1929 obituary on Berger from Milwaukee’s NAACP praising “the very broad and sympathetic views Mr. Berger always had regarding us as a race, the unbiased attitude of his paper, The Milwaukee Leader, and his interest in the welfare of all.” How could one square this NAACP assessment with Berger’s infamous 1902 declaration that “there can be no doubt that the negroes and mulattoes constitute a lower race—that the Caucasian and even the Mongolian have the start on them in civilization by many thousand years”? Maybe the Milwaukee NAACP was just saying something polite but inaccurate about an influential dead man?

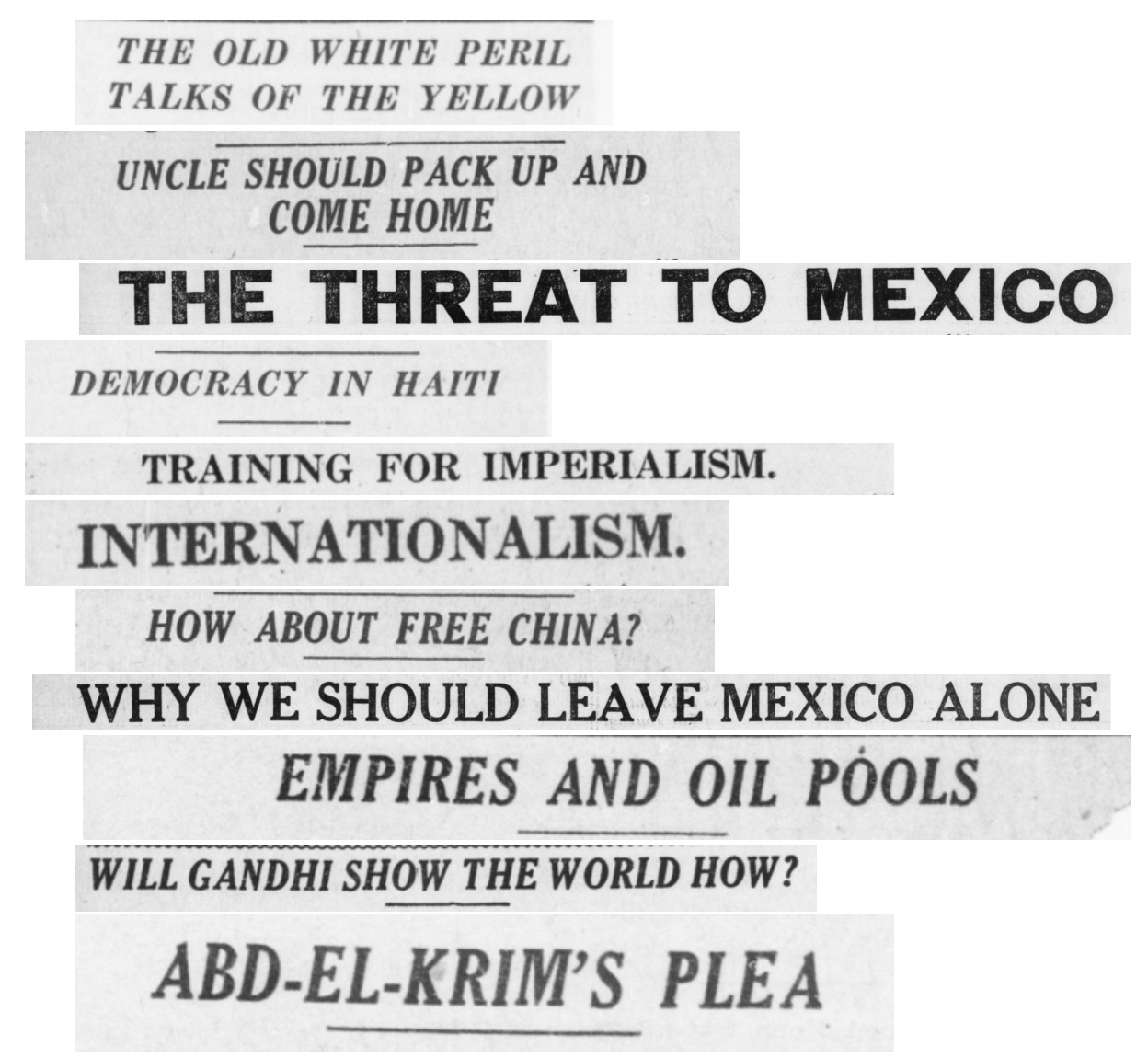

Searching for answers, I started systematically reading The Milwaukee Leader, the newspaper that Berger founded in 1913 and edited until he was killed by a trolley car in 1929. What I found surprised me. It turns out that generation after generation of historians had somehow managed to overlook a remarkable transformation: not only did Berger eventually ditch white supremacist views, but he and his paper became ardently anti-racist during the 1920s, a decade when most of white America in both the North and South actively embraced Jim Crow. Using his bully pulpit as America’s first Socialist congressman, Berger became one of the country’s highest-profile white fighters against lynching, racism, imperialism, and nativism.

This is an important story to tell. One-sided portrayals of Berger have long steered US radicals away from learning from our country’s most successful socialist organization: no other group has come close to replicating the Wisconsin socialists’ continued governance over almost five decades, their per capita recruitment to socialism, and their degree of leadership within organized labor and the broader working class. Nevertheless, as a comrade in Milwaukee wrote me a few weeks ago, “the activist attitude here and elsewhere has just been: Berger said racist things so Milwaukee socialists were racists. And then a lot of people just stop there.”

We can’t afford to keep dismissing sewer socialism, especially now that socialists are about to govern New York City and Seattle. This doesn’t mean we should paper over Berger’s initial white supremacist views, which activists today are obviously right to reject. Nor am I suggesting that the major reason to learn from sewer socialism is because of Berger’s later anti-racist praxis. My point is simple: the evolution of Victor Berger’s strategy and practice shows that there’s nothing inherently racist — and therefore politically disqualifying — about sewer socialism.

I focus here on Berger — and his paper’s support for Milwaukee’s long-forgotten Black socialists like William Bryant — not out of any dubious desire to rehabilitate a bigot, but because dismissals of Milwaukee’s rich socialist experience have hinged on Berger’s chauvinism. I’m also trying to fill a gap in the historiography. Whereas Berger’s anti-racist transformation has been entirely overlooked in the published literature — an erasure that has, in turn, erased the contributions of Milwaukee’s first Black socialists — various excellent studies have already shown that Socialist mayor Daniel Hoan (1916-1940) joined the NAACP and fought the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and that Milwaukee’s last Socialist mayor, Frank Zeidler (1948-1960), was race-baited out of office because of his egalitarian approach to city housing and “race relations.”

Finally, Berger’s evolution is in itself a remarkable, somewhat puzzling, and ultimately hopeful story. Why did someone committed to racial chauvinism for decades drop this at precisely the moment when so many European immigrants across the US were eagerly adopting and assimilating into white racism? It’s ironic that Berger has long been cited as evidence of American socialism’s inability to break from dominant racial views, when in fact his life is proof of the exact opposite dynamic.

Berger’s Pre-War Racism

The consensus story told about sewer socialism’s founder gets a lot right about his views up through 1912. Though race was not a central focus of Berger’s writings, those that do touch on this are mostly abominable. One finds here a mix of “scientific” biological racism with Eurocentric assumptions that every people was at a different stage of civilization, with “the white race” in the lead by orders of magnitude. His infamous 1902 article “The Misfortune of the Negro” repeats the racist myth — frequently used to justify lynchings — about the “many cases of rape which occur wherever negroes are settled.” And the following year he similarly referenced “sexual maniacs and all other offensive and lynchable human degenerates” in a 1903 resolution condemning lynchings that he submitted to the Socialist International. That same year, Berger published a letter from a Texas socialist leader opposing social equality arguing that the “independence” of racial groups from each other would increase under socialism.

Parallel to this, Berger — a German immigrant himself — fought hard for the Socialist Party to oppose Asian immigration. Arguing in 1907 that the United States “must remain a white man’s country,” he wrote that Karl Marx’s famous call “Workingmen of all countries, unite!” had hardened into a dogma disproven by the subsequent rise of Asian immigration, which was undercutting conditions for white workers: “Open the doors to Chinamen, Japanese and Hindoos, and we shall not have Socialism in 500 years. There has not been any perceptible change in the modes of thinking of the masses of Chinamen, Hindoos and Japanese in a thousand years.” In his view, this was not just a question of uneven socio-economic development: “Scientists tell us that the anatomy of the Jap is different from ours — it is more simian (ape-like).” At the 1910 Socialist Party convention he made a similarly xenophobic intervention. And as late as 1912, Berger was still fine including in a collection of his earlier writings claims like the “brilliant culture of our country” was “by right an inheritance of the white race.”

In response to these arguments, Black Socialist W.E.B. Du Bois justifiably criticized socialists for concerning themselves only “with the European civilization, with the white races” and concluded that “so long as the Socialist movement can put a ban upon any race because of its color, whether that color be yellow or black, the negro will not feel at home in it.”

According to a recent polemic by the Marxist Unity Group, Berger’s racist stances reflected the sewer socialists’ strategy of tailing popular consciousness instead of boldly leading it forward. It’s true that running to win elections, as Milwaukee’s socialists generally did, pressures any political current to center widely and deeply felt issues in its electoral campaigns — and that this always carries a risk of marginalizing controversial stances. But Berger’s vile statements weren’t the result of fudging internationalist principles for the sake of not alienating the masses. He was just genuinely racist at this time. Conversely, during these same years Berger did not hesitate to champion all sorts of other controversial or minoritarian positions, including socializing the means of production, advocating revolution, arming the people to overthrow capitalism through force, abolishing the Senate, and ending the power of the Supreme Court.

New York’s leading Black radical Hubert Harrison made this point in 1911, when he was still a member of the Socialist Party. Against those in the party who argued against incorporating immediate demands to alleviate the condition of Black people (supposedly this would be resolved in passing through socialism), Harrison noted that the party’s congressman Victor Berger was fighting for an old-age pension bill, a demand that had no chance of passing anytime in the foreseeable future.

For the sake of understanding Berger’s later evolution, it should also be noted that even in this pre-war period one can already find some relatively egalitarian notes in his writings and actions. Unlike the early Karl Marx, he never saw colonialism or imperialism as forces for progress. Berger’s first paper, The Social Democratic Herald, published numerous anti-imperialist pieces and as America’s sole Socialist congressman, the first bill he presented after his 1910 election was to demand the removal of US troops from the Mexican border.

In Congress, Berger also argued in favor of raising federal employee wages regardless of race and voted for federal supervision of primaries in the South to guarantee Black voting rights. Despite his racism, Berger in 1901 criticized the US government’s “failure to protect the negro.” His infamous 1902 article framed itself as an attempt to explain “the barbarous behavior of the American whites towards the negroes, and the contempt evinced for their human rights.” And the 1903 Texas socialist leader’s suggestion in The Milwaukee Leader about voluntary racial “independence” under socialism was part of a letter demanding that the Louisiana SP reverse its decision to segregate its membership into separate white and colored branches. In the Socialist Party’s National Committee, Berger accordingly voted against granting a charter to the Louisiana SP until it rescinded this Jim Crow provision. On the other hand, historian R. Laurence Moore notes that “evidently the National Committee tolerated the practice of segregation among its Southern branches so long as segregation was not made compulsory.”

“Colorblind” Transition to a New Stance: 1912—1918

In the years leading up to America’s entry into World War I, Berger’s positions on race began shifting. The dominant tenor of The Milwaukee Leader and his editorials increasingly became a “colorblind” socialism that stressed the “identity of interests” of all workers, that raised (but did not focus on) demands for racial equality, and that mostly (though not consistently) dropped the explicit racism of years prior.

Whereas he had previously assumed there would inherently be conflict and distrust between racial groups, by 1915 the Leader was denouncing “the poison of prejudice and the degrading sense of advantage, of a superiority that passes itself off as inborn. Far from hating one another by instinct, the alien races are often instinctively drawn to one another.”

That same year, Berger argued that the populist movements of decades prior had become powerful by making “it manifest to the small white farmers that they had an identity of economic and political interests with the negro renters.” Similarly, in 1912 the Leader published this response to employer plans to break a New York City waiters’ strike via non-white strikebreakers:

This matter of using color against color, race against race, is one of the most dangerous things in this country. We have people from every part of the globe. Some of them speak English; some of them do not. Some are black, yellow, red, white. … There is not a waiter in New York city who, whatever his color, has any interests apart from all the other waiters. This is not a race question, but a wages question, a question of class, and all of them belong to the working class.

Such an orientation failed to identify or challenge the specific burdens facing non-white people at work and in society, and it sometimes downplayed the extent to which white chauvinism in particular was the key obstacle towards building working-class unity. But compared to years prior, it was a real step forward. In that egalitarian spirit, Berger’s proposed old-age pension bill in Congress explicitly included Black people.

Berger and the Leader also began questioning the scientific basis of “scientific racism.” Articles in 1914 and 1916 cited Columbia anthropology professor Franz Boas’s pioneering new research challenging dominant theories about biologically superior races. And in line with Boas’s case that there was no such thing as a superior civilization, the Leader in 1914 published a piece arguing that,

race hatred is one of the lowest and meanest of human passions. A race may have more cunning than another, but the race that makes the accusation may have more bluff. … Until we learn to judge every individual on his own peculiar merits, we haven’t taken a first good step toward social intelligence.

It should be kept in mind that Milwaukee was still over 99 percent white at this time — not until World War I did a considerable number of Black people arrive. Yet as early as 1912 the Leader was arguing that experience in Milwaukee had demonstrated the falsity of predictions “that the colored people would not be able to exist as respectable citizens but would become parasites and degenerates.” Lamenting that few had yet joined the party or unions, the piece quoted socialist union leader Frank Webster’s case that “the colored men are not only welcomed in the industrial [union] organizations, but they have proven in all the states to be loyal to their cause.” And it concluded by highlighting that Black students had begun enrolling in Milwaukee’s schools and that various Black workers were now on the city payroll. This practical experience with Black people in Milwaukee seems to have helped undercut Berger’s racism, especially from 1918 onwards.

What else can explain Berger’s shift away from racism? It helped that he was a voracious reader and non-dogmatic thinker open to changing his views when presented with new evidence. “We must learn a great deal,” insisted Berger in 1905. When both personal experience and the latest scientific research from Boas challenged Berger’s racist priors, he began to reconsider. The fact that he was already a Marxist — an ideology with deeply egalitarian and universalist foundations — significantly facilitated this process. Indeed, even in Berger’s most-racist period he had acknowledged that his white supremacist stances constituted a break from, rather than continuity with, the views of Marx.

Finally, letters to the editor by Black socialists may have also contributed to Berger’s shift. In 1915, for instance, he published a letter to the editor ridiculing white supremacy and World War I, signed by “DE AFRICA”:

we all know that the white race has been the most murderous on earth. … Think of it—a civilization (?) overwhelmingly Christian (?) in the fratricidal struggles of Europe, and tell me why a Christian ought not to be ashamed of his religion. … Who would not rather be Tousaint L’Overture, Booker Washington, Paul Dunbar, Fred Douglas, W. P. DuBois or any good, honest, hard-working “nigger” than to be a “Christian” king?

Nevertheless, we shouldn’t exaggerate the extent of Berger’s anti-racist transformation up through 1918. One still can find some blatantly chauvinistic pieces in the Leader in this period. A 1916 editorial of his warned of the “yellow peril” of Asian immigration. Another suggested that while socialism would bring political and economic equality to all and that “to the Socialist all races and nations are equally dear,” nevertheless white people would continue to be “history’s great favorite” for “a long time.” Black people were sometimes condescendingly presented as passive and unthinking victims of oppression. And while a 1913 piece praised the intellectual and political “renaissance of Asia” and a 1916 editorial objected to singling out Japanese for immigration restrictions, Berger in this period had not yet broken from assumptions that “the white race” constituted the highest form of civilization. Not until the post-war upheavals in the US and abroad did Berger finally become a committed anti-racist fighter in words and deeds.

Against Black Oppression in Congress and Milwaukee: 1918-1929

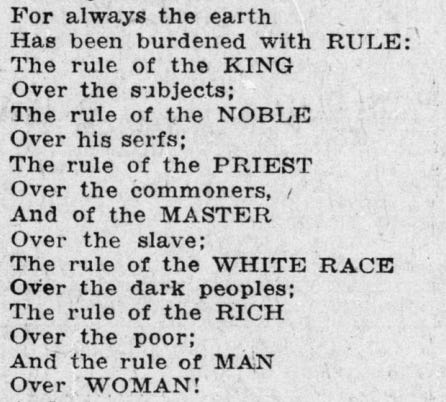

Sharply opposing the oppression of Black people and all forms of racial injustice became a regular theme of Berger and his newspaper during the war and especially throughout the 1920s. In addition to persistent calls for unity between “white, black, yellow workers,” the Leader week after week denounced race prejudice, the bogus claims of “race science,” lynchings in the south, white hate riots and discriminatory practices in the north, and the Ku Klux Klan nationwide, often on the front page.

A 1919 editorial in the Leader titled “A Nation’s Disgrace,” described in gruesome detail a recent lynching in Mississippi to question the myth that “we are so civilized, so democratic and so good” in America. “What intelligent person can expect that the Chinese, Japs, and other foreigners can look upon America from any other viewpoint than that we are brutal, half-civilized savages,” asked the author. The piece — soon reprinted in the Blade, Milwaukee’s main Black newspaper — concluded with a call to lead southern whites “out of the jungle and on to the highlands of Socialism.”

Other front-page pieces directly challenged the widespread racist claim that Black men were particularly inclined to rape: “Facts and evidence point in the opposite direction … They are certainly far less addicted than the American white group.” As a 1919 Leader editorial noted, “rape is no less rape because it is perpetrated upon black women.”

Berger’s paper also eventually started promoting thinkers who explicitly challenged the taboo — one shared by many anti-racist Black and white radicals of the era — around “social equality” (interracial coupling): “Intermingling of the races is inevitable and productive of good. … The time … will come when every thought of race will disappear.”

White racism — not just “racial divisions” in general — was forcefully challenged. One piece announced that the time had arrived “for another emancipation proclamation which will liberate the white race from its thralldom of pride and prejudice and bigotry.” Another reminded readers that “the great anthropologist, Franz Boas, has once and for all discredited the theory—or, rather, the superstition—that some races are inherently better or higher in the scale than others.”

Front-page pieces probed the sometimes subtle forms white racism took in the North, as well as the often justified suspicion of Black people towards white people after “so often [being] swindled by whites.” Another piece lampooned Northern white hypocrisy: “We in the North are still capable of shedding tears over a stage presentation of ‘Uncle Tom’—but if, at the same show, a Negro were to seat himself next to us, we would feel resentful and probably summon the usher, raise an uproar and demand that our seat be changed.” Racial divisions, Berger now argued, were one of the central reasons why America’s socialists and workers were “surely more poorly organized” than abroad.

A 1919 article in the Leader denounced the “race hatred” that American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers promoted within organized labor. Next year Berger published a report on a community forum in Milwaukee by NAACP leader Walter F. White who insisted that “as long as the negro worker is denied industrial opportunity, both by employers and labor unions, just so long will there be a deferring of adequate adjustment of relations between capital and labor.” The paper likewise ran reports countering racist myths like the idea that Black workers were responsible for lowering white worker wages. And it printed NAACP criticisms of the Typographical union for excluding Black workers, which meant that carrying a “union label” on a publication was “an advertisement that no negro’s hand is engaged in the printing of this magazine.”

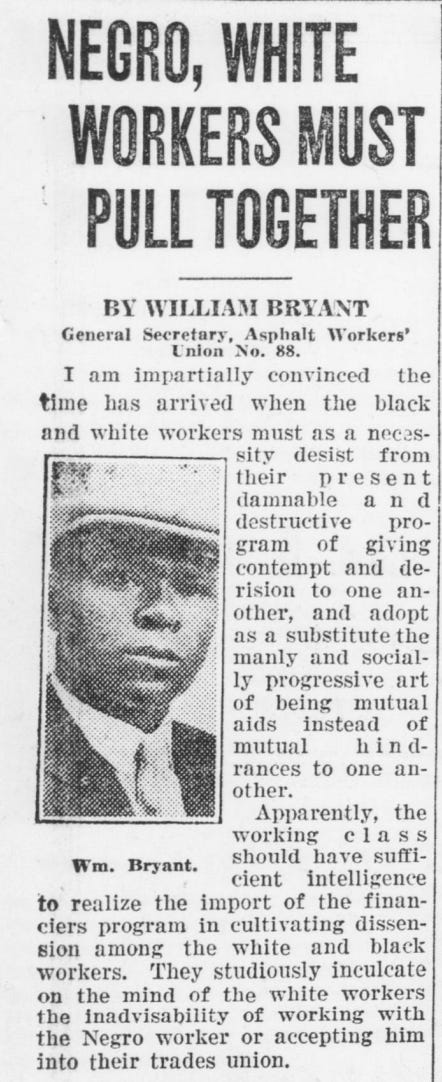

One frequent contributor to such arguments in the Leader was William Bryant, a Black Socialist Party member and General Secretary of Asphalt Workers’ Union Local 88, who consistently hammered on the need for unions to overcome their racism and accept Blacks into membership. In that same spirit, Berger in 1923 published Black Wobbly leader Ben Fletcher’s case that “the history of the organized labor movement’s attitude and disposition toward the Negro” was “a record of complete surrender before the color line.” White workers’ racism, not “Negro backwardness,” was pinpointed as the prime obstacle to unity. At the same time, the Leader consistently highlighted the work of A. Philip Randolph’s Black union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Moving beyond a simplistic “colorblind” class against class approach limited to economic demands, Berger and the Leader highlighted the work, ideas, and exposés of cross-class Black organizations like the NAACP, Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and the Urban League. Comprehensive analyses of the situation and struggles of Black people in the North and South became a frequent motif of the paper.

Condescending portrayals of ignorant victims gave way to a focus on Black cultural and political agency. The Leader ran articles on Harlem’s renaissance, on Black contributions to art and science, on W.E.B. Du Bois’ new theater troupe, and on the importance of Black-authored books for “colored children.”

On the political front, Berger in 1926 reminded his readers that “it is only a little over half a century since the Negroes emerged from chattel slavery. In that brief time, they have made marvelous progress against incredible odds.” As early as 1918, the Leader’s front page ran articles from the Black socialist newspaper The Messenger calling on “colored people” to join the Socialist Party to wage a battle for economic freedom and racial justice.

Critics can respond to all this by correctly noting that anti-racist words don’t necessarily translate into anti-racist deeds. But the Leader itself made this point. And all the available evidence suggests that Berger’s practice in these later years did generally correspond with his new views on race and racism. Research beyond the pages of the Leader and the congressional record is needed for a well-rounded account of his and the party’s practice, but what I’ve found so far is more than sufficient to disprove the myth that Berger was a lifelong bigot — or that the Socialist Party did nothing concrete to fight racism.

A front-page piece in 1920 highlighted that Grace Campbell, a Socialist Party candidate for the New York state legislature, was “the first colored woman to be nominated for a public office on a regular party ticket in the United States.”

Within Milwaukee, one of Berger and the Leader’s central fights in the early 1920s was from day one to keep the Ku Klux Klan out of Milwaukee, a battle they waged together with the local NAACP branch. For Berger, this fight was front-page news and he did not mince words: a man “cannot belong to a society organized to persecute Catholics, Jews, Negroes and foreigners— and at the same time call himself a Socialist.” Contrary to a longstanding historical myth — recently repeated in a Marxist Unity Group polemic against my research — the sewer socialists never ran an open KKK member for office; in fact, they immediately expelled the member in question once an internal party investigation got him to admit he had joined the Klan.

The Leader in the last decade of Berger’s life was full of articles about collaboration between Milwaukee’s Socialist Party and Black church leaders, Black neighborhood groups, and progressive Black organizations like the local Garveyite UNIA as well as the Urban League.

For instance, one 1920 article quoted Reverend Edward Thomas from the Church of God and the Saints of Christ, who at a Socialist mass meeting announced that the Leader was “only Milwaukee paper which gave his people a fair statement during the [nationwide] race riots of August, 1919.” As early as 1922 and 1924, the local UNIA branch was holding mass electoral rallies for Berger and other Socialist candidates. Eschewing Garvey’s back to Africa focus, UNIA leaders in Milwaukee like Ernest Bland and Carlos Del Ruy became members of the Socialist Party and agitated among Black working people for its candidates and its ideas of working-class unity.

I have not found any evidence that 1920s Black activists in Milwaukee were even aware of Berger’s earlier racist stances; keep in mind that most had arrived only since 1917. Milwaukee’s pro-Republican Black newspaper, the Blade, was remarkably favorable to the Socialists, highlighting their anti-racist writings and actions like Mayor Hoan’s 1917 efforts to stop local theaters from discriminating against Black people. In turn, the Leader used its platform to boost fights against discrimination, such as a last-minute rescinded invitation for the Urban League to participate in an upcoming parade. The paper also ran stories on how to improve the health of Milwaukee’s Black community and asked “what should be done to enhance the position of Negro women workers?”

Though historians like Philip Foner have long framed Berger’s approach to race as the polar opposite of Harlem’s radical intellectual leader Hubert Harrison, Black radical William Bridges reported in 1920 that Berger pledged his “moral and financial aid” to support the Liberty Party, a short-lived all-Black party in New York led by Bridges and Hubert Harrison. And four years later, Harrison travelled to Milwaukee to speak at a Socialist-led forum to generate Black support for and participation in Robert La Follette’s presidential campaign.

In addition to public events to recruit Black people to socialism — New York’s Black socialist leaders Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph were regular speakers in town on this topic — Milwaukee’s Socialist Party also clearly went out of their way to include “colored comrades” as speakers in predominantly-white events and forums. Black socialist union leader William Bryant was not only a common speaker at multi-racial open-air forums and electoral campaign events for Socialist candidates like Berger, he also chaired the party’s biggest mass meetings. And though it may not seem like a big deal today, it was an exceptionally anti-racist action at the time in 1921 to invite a Black socialist like Chandler Owen to be a headline speaker at the party’s massive and multiracial May Day celebration at the Milwaukee auditorium.

Black community members responded positively to this agitation. At a 1924 launch for a joint UNIA-Socialist canvass of Black neighborhoods, Bryant noted that “the colored voters of Milwaukee, as a matter of principle, have in recent years voted overwhelmingly Socialist. They have done so because they have apparently discovered that Socialism as practiced in Milwaukee embodies the sublime principle of impartiality.” Secondary sources confirm that Black Milwaukeeans did in fact overwhelmingly vote Socialist in the 1920s and 1930s. Even if Bryant’s claim that “90 per cent of the Negro voters in Milwaukee are Socialists” may have been somewhat exaggerated, the available evidence suggests that Black people were Milwaukee’s racial group that most consistently voted Socialist. And given that Republicans ran the state and that Milwaukee’s Socialists were never a solid majority — the party almost never had a City Council majority in its nearly 50 years of Socialist mayors — Black electoral support can’t be explained away simply as a pragmatic “bet on the winning horse.”

Discrimination and inequality for Black people did not suddenly disappear in Milwaukee. Much more archival research is needed to uncover what Socialist practice looked like beyond the pages of the Leader, but Berger and his paper by now were clearly on the side of anti-racist progress. In 1925, for instance, the paper’s report on the recent Wisconsin Federation of Labor convention highlighted that “a resolution deploring ‘color prejudice and race discrimination’ in certain state trade unions was introduced by William Bryant, Milwaukee Negro. He argued that dangerous division in the ranks of labor results from race discrimination.”

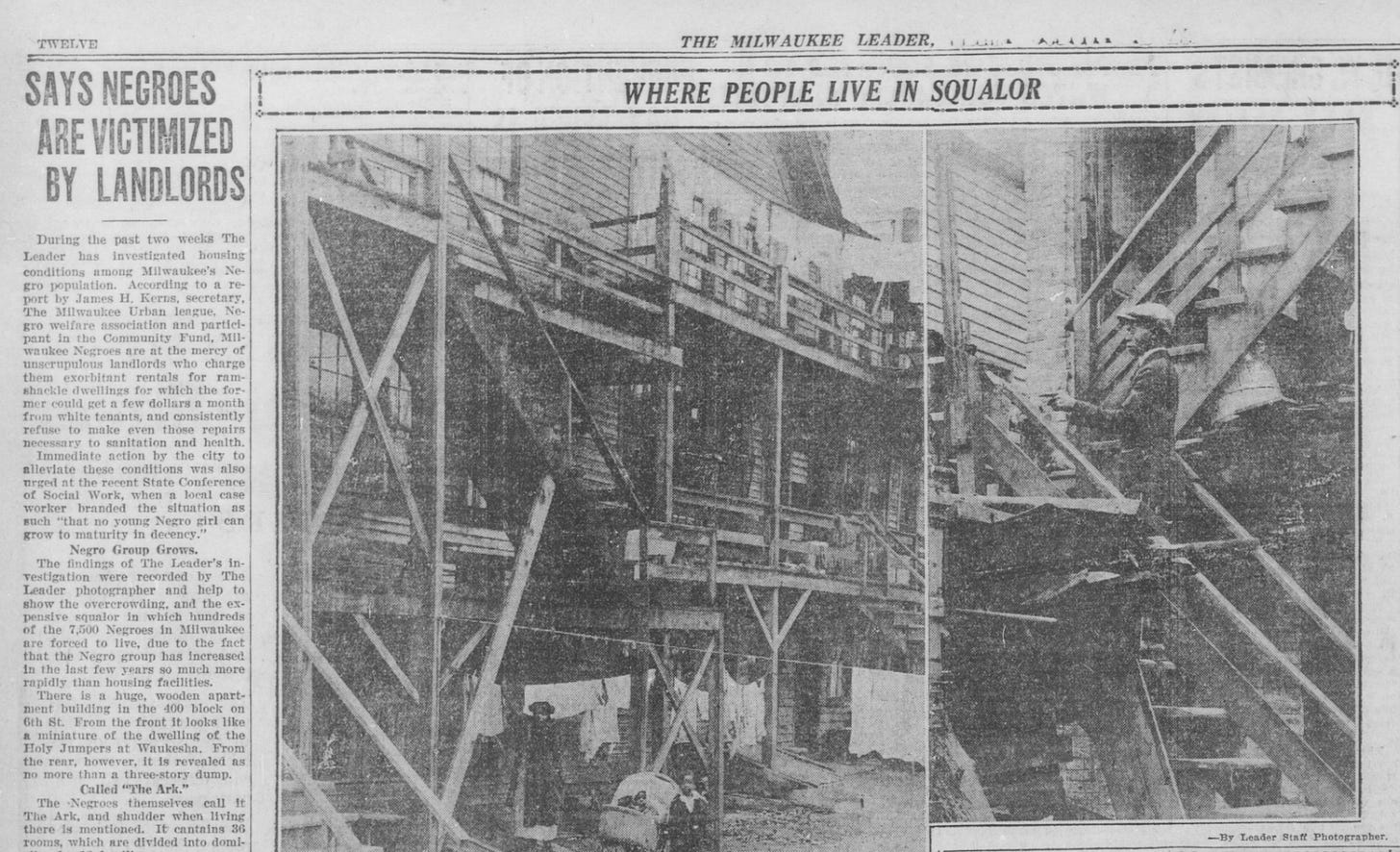

Unequal housing was another major theme. While various secondary sources say that a Socialist-supported low-income co-operative housing project in 1921 banned Black people, I didn’t find any primary sources confirming this. In 1924, the Leader boosted the (ultimately successful) protest efforts by the local NAACP and Reverend Edward Thomas to stop the Milwaukee real estate board’s push for “a certain section of the city [to] be segregated as a ‘black belt.’” That same year, as the Leader detailed, Mayor Hoan suggested to Black activists Ardie and Wilbur Halyard that they start a building and loan association to help Black Milwaukeeans — who were systematically denied loans from banks — buy homes “farther out” from “ramsackle downtown.” With Hoan’s active backing and help navigating the state bureaucracy, the Halyards founded Wisconsin’s first Black-owned bank. Five years later Wilbur Halyard authored the NAACP’s condolence letter for Berger.

In 1925, Berger wrote a long article summarizing research findings on dire housing conditions for Black people in Dallas, with the suggestion that a similar study be conducted in Milwaukee. Next year the Leader published such a study together with the Urban League in a multi-part exposé.

Parallel to this, Berger attacked capitalist newspapers for always highlighting the race of Black criminals while never doing the same for whites: “Why do not the papers say that ‘John Smith, white,’ is accused of this and that.” In 1924, the paper celebrated the hiring of the city’s first Black police officer, Judson Minor, while lamenting that Socialists on the City Council had lost their fight against hiring 40 new cops. Two years later the Leader reported that Minor had announced his resignation, “saying he was unable to withstand the campaign of nagging and false complaints lodged against him.”

One of the boldest anti-racist actions taken by Berger’s Leader was its vigorous defense of Black reverend and Socialist ally Edward Thomas, who on the night of September 13, 1925 fatally shot a white man, Lawrence Bucholz, and almost killed another, William Sigfried. The spark was a car accident between Thomas and Bucholz. After the accident, according to Sigfried and Bucholz’s female companion, the Reverend “began to curse” invectives. Thomas drove away, but Bucholz followed. Upon arriving at Thomas’ house, Buchotz opened the Reverend’s car door and demanded he apologize. Thomas refused. What happened next was the subject of trial for first degree murder — persecuted by the state of Wisconsin — and a press campaign in the Leader.

Aware that lynchings across the US had been started for far less than killing a white man, the Leader immediately jumped to Thomas’ defense, highlighting the Reverend’s upstanding character and his insistence that he had acted in self defense:

Sympathy is felt for the Rev. Thomas. Bucholz, the man he is accused of killing, was powerfully built and had a reputation for great strength. The first reports that Thomas used profanity was denied today by his acquaintances, who said that such language was in no way habitual with him. He had a good reputation among both the colored population and many others in business and public life, it is said, and his interest in the city’s welfare brought him the appointment to a place on the Sane Fourth commission by Mayor Daniel W. Hoan.

During the trial, Mayor Hoan and other socialist elected leaders appeared as character witnesses for the defendant and the city’s assistant district attorney acted as one of Thomas’ lawyers. In a front-page story on the trial’s closing session, the Leader highlighted the call from the Reverend’s lawyer to the jury to “cast aside your prejudice against this man because he is colored and weigh him on the same scales of justice as you would want to be weighed upon.”

The Leader’s closing coverage did not hide where its sympathies lay:

The defendant told an apparently straightforward story and several times had to stop when his sobbing interrupted him. “I would not have shot if I could have helped it,” he said. “These two men rushed over to me, opened the door of my machine, and took several punches at me. I was afraid they would kill me and I then fired.”

The jury found Thomas not guilty, an astounding win for racial justice in a decade when such wins were exceedingly rare.

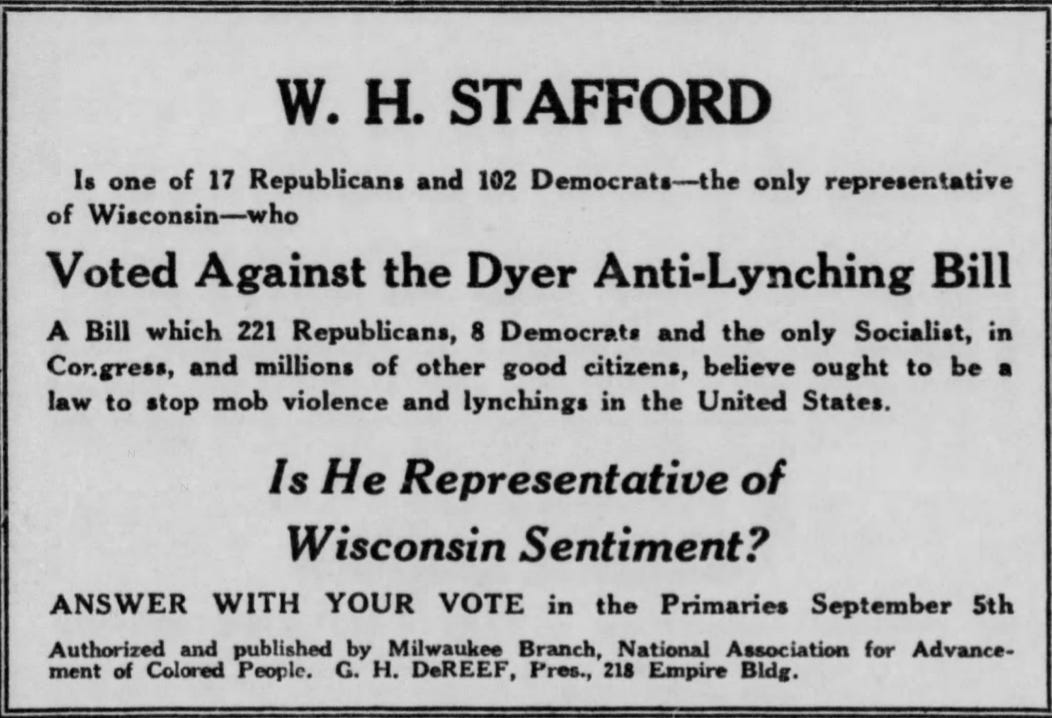

Berger’s egalitarianism was not limited to the written page. From 1919 onwards, anti-racism was a major theme of Berger’s campaigns for Congress and his work within it. The first plank in his successful 1922 congressional campaign opposed “race hatred” and the Ku Klux Klan. His editorials stressed that his incumbent electoral rival, W.H. Stafford, had “voted against the antilynching bill.” In 1926 and 1928, Berger introduced and fought hard for a new anti-lynching bill, which he boasted to the House was “stronger than any other” ever proposed because it had “teeth in it.” The following year he introduced a bill to outlaw the KKK.

What explains Berger and the Leader’s shift towards foregrounding the fight against Black oppression in the 1920s? It can’t be attributed primarily to electoral opportunism, since Black people only constituted about one percent of Milwaukee and the congressional district he was running in. Given the pervasiveness and deepening of racist assumptions among so many white voters in this era, the path of least resistance would have been to avoid any racially egalitarian planks. But, contrary to recent polemical claims about “tailing” racism, Berger’s political current chose to fight. Largely because of their proven track record of effectively delivering material improvements to Wisconsin workers, by the early 1920s they had forged enough political space for themselves to take up minoritarian stances on racism without automatically tanking their electoral chances.

Unfortunately, there are no formulas for how to effectively combine fights against oppression with majoritarian working-class politics — it’s always context specific. Organizing efforts, especially outside of the electoral arena, for not-yet-majoritarian demands are often crucial for shifting public opinion and winning changes. Yet just speaking truth to power doesn’t have much of a track record of success. And Milwaukee’s experience — like Zohran’s recent campaign — shows that centering widely and deeply felt issues in electoral campaigns can sometimes make it possible to simultaneously uphold more controversial stances that benefit a particularly oppressed group.

Another factor in Berger’s turn was the anti-German scapegoating he and his Milwaukee comrades were subjected to for opposing World War I — a stance that landed Berger a 20-year federal prison conviction (eventually overturned by the Supreme Court). Berger framed these jingoistic attacks against him and Milwaukee Socialists as a form of “race hatred” and it seems likely that his personal experience of persecution deepened his empathy for other persecuted groups.

Finally, Berger’s transformation — a turn taken also by the Socialist Party of America nationwide after 1917 — cannot be separated from the dramatic growth of Black radicalism during and following World War I. Assumptions of Black “passivity” or “backwardness” were clearly challenged by this rising tide of organized radicalism and, more specifically, by the interventions of Black socialists like William Bryant, W.E.B. Du Bois, Chandler Owen, and A. Philip Randolph — the latter of whom remained one of America’s most influential Black radicals and became the “father of the civil rights movement” by initiating Black mass actions for equality in the 1940s and by training many leaders of the 1960s freedom struggles.

It’s not surprising that Black militants led the fight for racial justice in Milwaukee. But it’s to Berger’s credit that he followed.

Pro-Immigrant, Anti-Imperialist: 1921-1929

Berger had always been consistently anti-imperialist. And this orientation deepened after the war, as he and the Leader lambasted American theories of “manifest destiny,” mocked anti-Turkish racism and “yellow peril” rhetoric, called on the US to accept Filipino and Haitian independence, praised Emiliano Zapata and opposed US intervention in Mexico, defended Moroccan anti-imperialist leader Abd-El-Krim, advocated Indian independence and praised Pandit Jawahari Lal Nehru, and stood in solidarity with China’s struggle for national independence and democracy. One quote about Morocco’s revolutionary struggle for independence should suffice to give a sense of the tenor and content of Berger’s anti-imperialism:

Our Wall Street press paints Abd-El-Krim and his Riff tribesmen as savages who threaten the sacred ideals of white civilization in Africa. The Wall Street editors overlook that the British tories used to paint the fathers of the American revolution just like that. … His fight for national independence is as just as the struggle of the 13 colonies against British rule. In election campaigns, our capitalist editors always tell us that America is dedicated to the proposition that all men have equal rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. They don’t talk like that when organized labor tries to put this doctrine into effect, or when small nations that excite the greed of our hundred percenters defend their independence.

After the war Berger also underwent a major shift in his views and practice on Asian immigration to the US. As early as 1921, the Leader condemned “the anti-Japanese campaign” in America. Berger also published a report on a talk in Milwaukee from socialist philosopher Bertrand Russell about China: “Thoughts of yellow perils, ‘chinks’ and the like were straightway put to route [by Russell] … Instead of the Chinese being a danger to us, we are a danger to the Chinese, he said … they were more civilized than our western civilization.”

Immigration became a particularly immediate question for Berger in the spring of 1924, once Congress began debating the Johnson-Reed Act, which would entirely ban Asian immigration and significantly cap southern European immigration. Berger wrote that Congress “will scarcely be willing to open the [immigration] gates wide—they are too much afraid somebody with a little brains in his skull might sneak in.”

While initially clarifying that he opposed “unrestricted Japanese immigration” on economic grounds, Berger insisted that “the Japanese and the Americans have the same forebears. All are humans—brothers—and there is no reason why they should hate one another. Race prejudice is silly and unworthy. It is a fine thing for people of different races to intermingle. It is good for all, since it broadens their minds.”

For the Leader, Berger’s opposition to the Johnson-Reed Act was front-page news. Berger declared that he “takes no stock in the so-called superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race and that the immigrant has been largely responsible for the growth of this country.” In May, Berger turned these words into deeds by voting against the Act. In an explanation in the Leader, Berger emphasized that he opposed both the Japanese exclusion provision and the broader restrictions, insisting that “the immigration bill … is an inhuman measure.” In that same spirit, Berger subsequently published coverage of Japanese protests against US discrimination — “speaking frankly the Americans are a foolish people”— as well as a subsequent piece arguing for an end to the US immigration ban on Hindus.

Asian peoples abroad were no longer seen either as threats to whites or helpless victims of imperialism, but as agents for both democracy and socialism. In 1918, the Leader published a guest editorial by Indian revolutionary Lajpat Rai, which concluded that European and American leaders “care only for the white race” and failed to “realize that the greater part of humanity lives in Asia and Africa.” A decade later, Berger’s editorial on Nehru in India underscored that “the Socialist movement is world-wide. It is growing everywhere, and it is not confined to Europe and America. … Oriental countries are going to insist upon their rights, and white countries will have to quit treating them as children, or there will be trouble.”

Not all of Berger’s formulations or assumptions about “the Orient” have stood the test of time. Berger’s speeches to Congress sometimes used antiquated rhetoric like “backward peoples” — including in his House-floor denunciations of imperialism. And while he broke from the ideas of racial or national superiority, Berger periodically referenced dubious ideas about supposedly longstanding cultural essences. As a 1914 editorial published in the Leader put it, “One [people] may have more culture, but the other may excel in simple honesty. And when it comes to summing up all the virtues, faults and capabilities of each race, one about equals the other.” Along those lines, in a 1924 speech to Congress against alcohol prohibition, Berger replied to claims that alcohol hindered productivity and morality by arguing that despite being such heavy drinkers, northern Europeans demonstrated higher amounts of certain “essentials of civilization” like “usefulness and virtue” than abstinent peoples like Muslims and Hindus.

Such isolated formulations, however, were the exception that proves the rule. Over again throughout the 1920s, Berger and the Leader questioned the idea that American or European societies were more culturally advanced. As Berger wrote in 1920: “We may yet see the white race returning to Africa and China for some better substitute for its downfallen civilization.” Questioning the “so-called civilization” of “the white race,” in 1922 he reminded readers that “some of the best ideas have come from [the Orient] — from peoples who do not have a white skin” and argued that India’s resistance movement had the potential to point the way forward for all countries.

By the post-war period, Berger and his paper had made it very clear where they stood in the battle against racism at home and abroad. As one Leader article underscored, “whoever sets Gentile against Jew, white against black, the races of the West against those of the East, approaches mankind with the kiss of the betrayer and the dagger of the assassin. There can be no compromise, no shadow of wavering on this supreme issue.”

Conclusion

Recent leftist claims that sewer socialism necessarily requires “tailing” the racism of white workers have little factual basis. Nor do assertions that Victor Berger was an incorrigible racist.

In the face of the evidence I’ve provided here, some critics may concede that Berger’s racial stances eventually evolved, while arguing that his earlier white supremacist ideas nevertheless disqualify him and his party from being any sort of positive reference point for today. But such a line of argument would be hypocritical since all socialist traditions at some point in the past held some reactionary ideas and practices on race, gender, or sexuality. A recent scholarly study, for example, convincingly shows that Karl Marx never broke from his belief that “‘races’ endowed with superior qualities would boost economic development and productivity, while the less endowed ones would hold humanity back. … For present-day standards, the racism displayed by Marx and Engels was outrageous and even extreme.”

If you repudiate Berger because of his pre-war racism, you have to also repudiate Marx — especially since Berger eventually went further than Marx in dropping racist assumptions. A more reasonable approach is to unequivocally acknowledge and reject all the chauvinist views of our socialist predecessors, while showing that there’s nothing inherently racist, sexist, or homophobic about their broader political strategy. Ironically, this has been precisely the approach taken towards Marx’s chauvinism (and the Black Panthers’ sexism) by some of the very same Left activists and currents who have recently used Berger’s racist statements as an excuse to entirely dismiss sewer socialism.

And if you repudiate Berger, you also have to repudiate Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party’s left-wing standard bearer. Challenging claims that racism was only a problem among the Socialist Party’s Berger-led right wing — an interpretation still commonly made today — historian R. Laurence Moore showed in 1969 that in the early 20th century “almost all [white] socialists regarded Negroes as at that time occupying a lower position on the evolutionary scale than the white.” In 1904, while otherwise advocating for “colorblind” socialism, Debs wrote that “the Negro, like the white man, is subject to the laws of physical, mental, and moral development. But in his case these laws have been suspended. Socialism simply proposes that the Negro shall have full opportunity to develop his mind and soul, and this will in time emancipate the race from animalism, so repulsive to those especially whose fortunes are built up out of it.” And instead of challenging the myth of Black male “rape-maniacs,” he argued that the Black “rape-fiend” was “the spawn of civilized lust” in America.

My point here is not to suggest that Debs was as racist in this period as Berger or that Debs never overcame those ideas. The point is just that if you’re okay celebrating Debs’ positive contributions to the movement, you should be able to do the same for Berger.

Vilifying sewer socialism in the name of anti-racism not only ignores Berger’s later evolution, it also ignores the political agency and assessments of Milwaukee’s Black organizers like William Bryant, Carlos Del Ruy, Reverend Edward Thomas, and Ardie and Wilbur Halyard. Each of these leaders fought for a more egalitarian city, each pulled sewer socialism towards anti-racism, each enabled socialism’s widespread popularity among Milwaukee’s Black working class, and each saw Berger and his current as a force for racial justice. Unless you think these Black activists were dupes, it makes sense to trust their on-the-ground assessments more than subsequent historians or activists with obvious factional axes to grind.

Further research is needed to assess the extent to which Milwaukee’s socialists — in the party, in the unions, in neighborhoods — consistently put their anti-racist ideas into practice. It may turn out that the empirical record confirms the historical consensus that Milwaukee’s white Socialists even at their best never became as consistent and committed to fighting racial injustice as American Communists. But, either way, this article has shown that since there’s nothing inherently racist or “tailist” about sewer socialism, it’s wrong for leftists today to dismiss sewer socialism on these grounds.

Instead of clinging to debunked myths and doctrinaire formulas, our movement would do well to grapple with the broader strategic lessons of America’s most successful socialist organization on how to build mass working-class power in our country’s unique context. Today’s exceptional challenges and openings demand that we think more rigorously, organize more resolutely, and fight more widely than we’ve ever done before.

More

Please share this article widely! As you can hopefully tell, it took a lot of time and research to track down so many primary sources (linked to above as hyperlinks) — it’d mean a lot to me if you could share this piece on social media, to friends, in organizing chats, etc.

Are you a high school student in NYC — or know one? High school organizers are circulating this pledge to walk out when Trump surges ICE.

Organizing against ICE is heating up in NYC, sign up here to get updates from the Hands Off NYC coalition.

If you haven’t joined DSA yet, today’s a great day to do so.

Happy holidays! Hope you get a chance to relax and recuperate, we’ll need all the energy we can muster for the battles ahead in 2026.

Incredibly useful piece here. I think its particularly worth considering the transformation of Berger in the 1910s for how it tracks with many transformations socialists occassionally have to go through - from simple assumption that a system of socialism will rise all tides thus allowing for ignorance of race specific politics to understanding that white supremacy is part of that capitalist system we are looking to overturn.

Intersectionalism isn't just about overturning your biases as Berger did in the 1910s advocate for a color-blind socialism - we need to practice what he did after 1918 in making the direct anti-racist argument that comes with transforming our society.

Actual historical research > polemics