Socialists in City Hall? A New Look at Sewer Socialism in Wisconsin

It’s been done before—we can do it again in New York and beyond

In 1910, Milwaukee’s socialists swept into office and they proceeded to run the city for most of the next fifty years. Though ruling elites initially predicted chaos and disaster, even Time magazine by 1936 felt obliged to run a cover story titled “Marxist Mayor” on the city’s success, noting that under socialist rule “Milwaukee has become perhaps the best-governed city in the US.”

This experience is rich in lessons for Zohran Mamdani and contemporary Left activists looking to lean on City Hall to build a working-class alternative to Democratic neoliberalism and Donald Trump’s authoritarianism. But the history of Milwaukee’s so-called sewer socialists is much more than a story simply about local Left governance. The rise and effectiveness of the town’s socialist governments largely depended on a radical political organization rooted in Milwaukee’s trade unions and working class.

Nowhere in the US were socialists stronger than in Milwaukee. And Wisconsin was the state with the most elected socialist officials as well as the highest number of socialist legislators (see Figure 1). It was also the only state in America where socialists consistently led the entire union movement — indeed, it was primarily their roots in organized labor that made their electoral and policy success possible, including the passage of 295 socialist-authored bills statewide between 1919 and 1931.

Contrary to what much of the literature on sewer socialism has suggested, the party’s growth did not come at the cost of dropping radical politics. That they didn’t get closer to overthrowing capitalism was due to circumstances outside of their control, including relatively conservative public opinion. And the fact that they did achieve so much was because they flexibly concretized socialist politics for America’s uniquely challenging context.

The Rise of Sewer Socialism

Sewer socialism’s rise was far from automatic or rapid. Though Milwaukee’s largely German working class was perhaps somewhat more open to socialist ideas than some other ethnicities, a quantitative study of pre-war US immigrant voting found that Germans were negatively correlated with socialist votes nationwide.

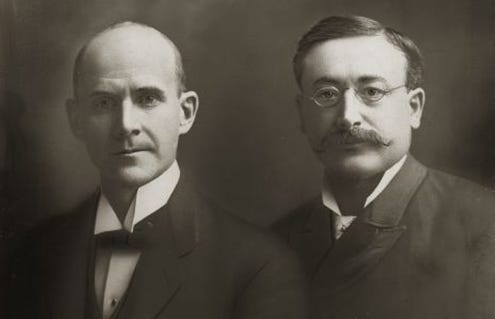

Figure 2 captures the party’s slow-but-steady rise over many decades. Here’s how the party’s founder, Victor Berger, described this dynamic in a speech following their big 1910 mayoral election victory:

“It took forty years to get a Socialist Mayor and administration in Milwaukee since first a band of comrades joined together. … It didn’t come quickly or easily to us. It meant work. Drop by drop until the cup ran over. Vote by vote to victory. Work not only during the few weeks of the campaign, but every month, every week, every day. Work in the factories and from house to house.”

Milwaukee’s history is a useful natural experiment for testing the viability of competing socialist strategies in the US. Both moderate and intransigent variants of Marxism were present and the latter had nearly a two-decade-long head start. The Socialist Labor Party (SLP) was the only game in town from 1875 onwards until Berger, a former SLP member, founded a more moderate rival socialist newspaper, Vorwärts (Forward), in 1893.

By the early nineties, the SLP under the leadership of Daniel De Leon had crystallized its strategy: run electoral campaigns to propagate the fundamental tenets of Marxism and build industrial unions to displace the reformist, craft-based American Federation of Labor (AFL). Had American workers been more radically inclined, the SLP’s strategy could have caught on — indeed, something close to this approach guided the early German Social Democracy as well as revolutionary Marxists across imperial Russia. But by 1900, Berger’s Social Democratic Party (SDP) had clearly eclipsed its more-radical rivals.

Pragmatic Marxism

What were the politics of Berger’s new current? Berger and his comrades are usually depicted as “reformists” for whom “change would come through evolution and democracy, and not through revolution.” In reality, the sewer socialists were — and remained — committed Marxists who saw the fight for reforms as a necessary means not only to improve the lives of working people, but also to strengthen working-class consciousness, organization, and power in the direction of socialist revolution in the US and across the globe.

Here’s how Berger articulated this vision in the founding 1911 issue of The Milwaukee Leader, his new English-language socialist daily newspaper: “The distinguishing trait of Socialists is that they understand the class struggle” and that “they boldly aim at the revolution because they want a radical change from the present system.”

Reacting against De Leon’s doctrinaire rigidity and marginality, Berger consciously sought to Americanize scientific socialism. Berger argued that socialists in the US “must give up forever the slavish imitation of the ‘German’ form of organization and the ‘German’ methods of electioneering and agitation.” Since the specifics of what to do in the US were not self-evident, this strategic starting point facilitated a useful degree of political humility and empirical curiosity.

One of the things Berger learned was that socialist propaganda would not widely resonate as long as most American workers remained resigned to their fate. This, he explained, was the core flaw in the SLP’s assumption that patiently preaching socialism would eventually convince the whole working class:

The most formidable obstacle in the way of further progress—and especially in the propaganda of Socialism—is not that men are insufficiently versed in political economy or lacking in intelligence. It is that people are without hope. … Despair is the chief opponent of progress. Our greatest need is hope.

It was precisely to overcome widespread feelings of popular resignation that the sewer socialists came to focus so much on fights for immediate demands, both at work and within government. Since “labor learns in the school of experience,” successful struggles even around relatively minor issues would tend to raise workers’ confidence, expectations, and openness to socialist ideas.

It was easy to play with “revolutionary phrases,” but Berger noted that this did not do much to move workers closer to socialism. While it was important to continue propagating the big ideas of socialism, what America’s leftists needed above all was “concrete political achievements, not theoretical treatises ... less mouth-work, more footwork.” Armed with this orientation, Berger and his comrades set out to win over a popular majority — starting with Milwaukee’s trade union activists.

Rooting Socialism in the Unions

By the time Berger arrived on the scene, Milwaukee already had a rich tradition of workplace militancy and unionism. Crucially, Berger’s current sought to transform established unions rather than enter into competition with them by setting up new socialist-led unions, as was the practice of the SLP and, later on, the Wobblies.

Years of hard work within the unions paid off. In December 1899, Milwaukee’s Federated Trades Council elected an executive committee made up entirely of socialists, including Berger. For the next quarter century, the leadership of the party and the unions statewide formed an “interlocking directorate” of working-class socialists involved in both formations. Nowhere else in the US did socialists become so hegemonic in the labor movement as they did in Milwaukee and Wisconsin.

A historian of Milwaukee unions notes the “inheritance Socialists bequeathed to the labor movement”: democratic norms; support for industrial (rather than craft) unionism; the absence of corruption; support for workers’ education; and strong political advocacy. Wisconsin’s socialists could not have achieved much without their union base. And precisely because they had succeeded in transforming established AFL unions by “boring from within,” they fought a relentless two-front war nationally against the self-isolating dual unionist efforts of left-wing Socialists and the Wobblies, on the one hand, and the narrow-minded AFL leadership of Samuel Gompers, on the other.

Building the Party

The anti-Socialist Milwaukee Free Press ruefully noted in 1910 that “there would not today be such sweeping Social-Democratic victories in Milwaukee if that party did not possess a solidarity of organization and purpose which is unequaled by that of any other party in the county, or, for that matter, in the state.”

Building this machine took years of experimentation and refinement under the guidance of Edmund Melms, an affable factory worker. Such a focus on organizing, with its focus on developing new working-class leaders, was crucial for helping Milwaukee’s socialists avoid the constant turnover and churn that undermined so many other SPA chapters.

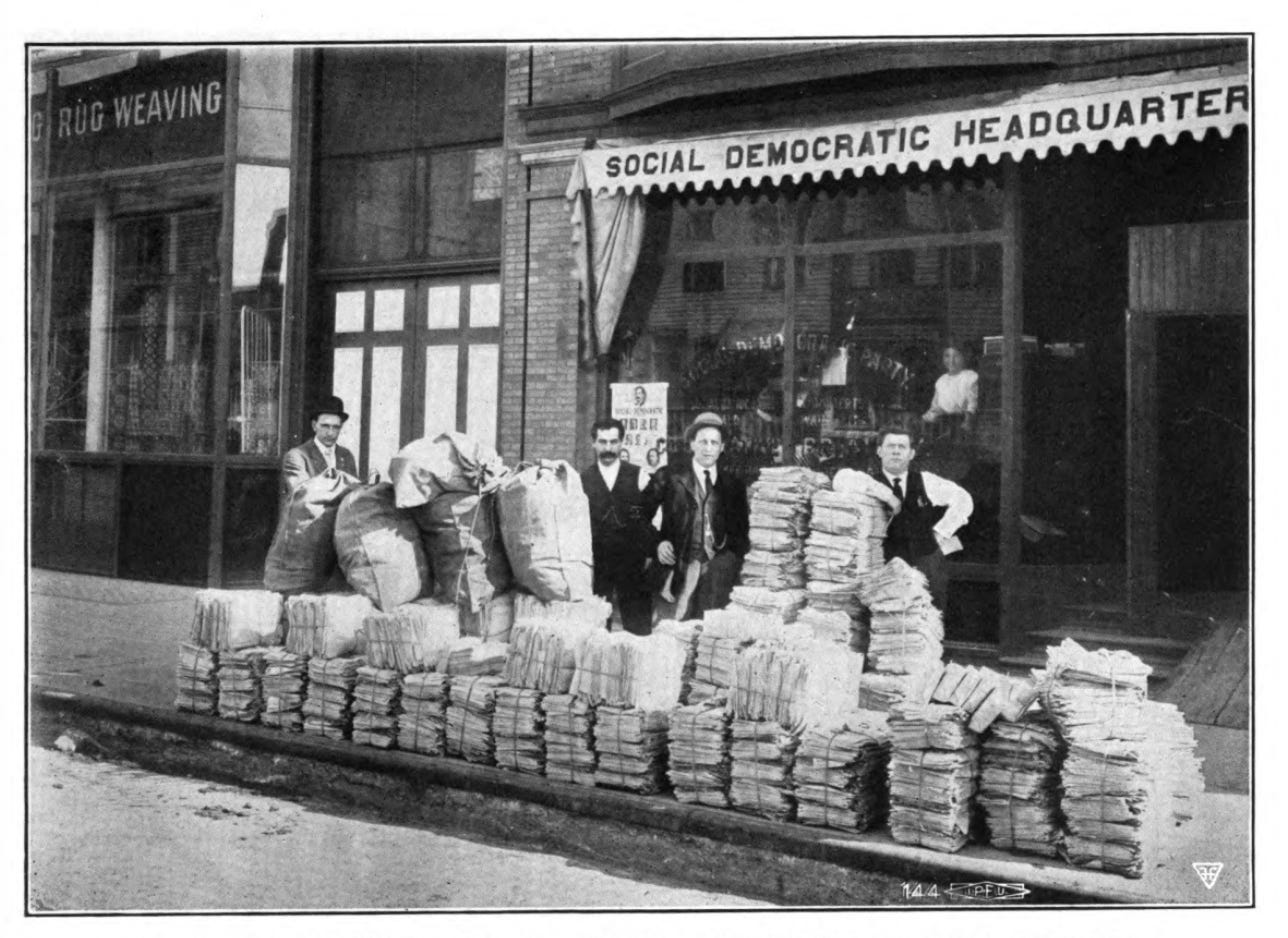

One of Melms’s organizational innovations was the party’s soon-to-be famous “bundle brigade.” During electoral campaigns, between 500 and 1,000 party members on Sunday mornings would pick up the SDP’s four-page electoral newspaper at 6 a.m. and deliver it to every home in town by 9 a.m. No other parties attempted anything this ambitious because they lacked sufficient volunteer capacity, not just for delivery but also for determining the language spoken in each house; party members would have to canvass their neighborhoods ahead of time to determine whether the house should receive literature in German, English, or Polish.

Melms’s second innovation was to hold a Socialist carnival every winter. These were massive events with over 10,000 participants, attracting (and raising funds from) community members well beyond the SDP’s ranks. In addition to these yearly carnivals, the party held all sorts of social activities which helped grow and cohere the movement. These included picnics, parades, card tournaments, dress balls, parties, concerts, baseball and basketball games, plays, and vaudeville shows. And some party branches were particularly proud of their singers. As one participant recalled, “Did you love song? Attend an affair of Branch 22.”

Whereas patronage and graft greased the wheels of other party machines, the socialists had to depend on selflessness derived from political commitment. While most people who voted for the SDP were interested primarily in winning immediate changes, there were also additional, loftier motivations undergirding the decision of so many working-class men, women, and teenagers to do thankless tasks like getting up early on cold Sunday mornings to distribute socialist literature. Historian-participant Elmer Beck is right that “the dreams, visions, and prophecies of the [Milwaukee] socialists … were an extremely vital factor in the rise of the socialist tide.”

Message and Demands

With its eyes planted on the goal of winning a majority of Milwaukeeans and Wisconsinites to socialism, the SDP was obsessed with spreading its message. Between 1893 and 1939, the party published twelve weekly newspapers, two dailies, one monthly magazine, as well as countless pamphlets and fliers.

Class consciousness was the central political point stressed in all the party’s agitation and publications — virtually everything was framed as a fight of workers against capitalists. Linked to this class analysis was a relentless focus on workers’ material needs: for instance, one of the SDP’s most impactful early leaflets was directed at working-class women: “Madam—how will you pay your bills?” This relentless focus on workers’ material needs was one of the key reasons the SDP was able to build such a deep base. Indeed, the party’s ability to recruit — and retain — so many workers depended on delivering tangible improvements to their lives (unlike so many other SPA chapters, who had to rely on ideological recruitment alone).

After 1904, immediate demands took on an increasingly central place in the SDP’s election campaigns. Had Milwaukee’s socialists lost sight of their socialist goals? Hardly. Up through its demise in the late 1930s, the party never ceased propagandizing for socialism and proposing ambitious but not-yet-winnable reforms. But Milwaukee’s sewer socialists believed that running to win in electoral contests — and seriously fighting to pass policy changes once in power — made it possible to recruit a larger, not smaller, number of workers to socialist politics.

The comparative data on party membership bears out this hypothesis. By 1912, roughly one out of every hundred people in Milwaukee was a member of the Social Democratic Party. No other city in America had anything close to this level of strength; in contrast, New York City, another socialist bastion, had one member for every thousand inhabitants. Had the Socialist Party of America been as strong as Milwaukee’s SDP, it would have had about one million members — roughly the same size as German Social Democracy, the world’s largest socialist party.

In a challenging American political context, Wisconsin’s socialists pushed as far as possible without losing their base. Rigorous comparative histories of US leftism have shown that all of the most successful instances of mass working-class politics in America have adopted some form of this kind of pragmatic radicalism, including Minnesota’s Farmer-Labor Party, New York’s Jewish immigrant socialism, and the Popular Front Communists of the late 1930s.

Nevertheless, far left socialists elsewhere in the country — whose tactical rigidity was both a cause and consequence of their weaker roots in the class — frequently criticized their Wisconsin comrades’ supposed “opportunism.” In 1905, for example, the national leadership of the SPA expelled Berger from the body for suggesting in an article that Milwaukeeans vote against a right-wing judge in a non-partisan race that the party did not have the capacity to contest. Berger lambasted this “heresy hunt without a heresy” and he succeeded in winning back his post through an SPA membership referendum, the national (and local) party’s highest decision-making structure. Episodes such as these led the SDP to jealously guard its autonomy from national Socialist Party of America structures that periodically succumbed to leftist dogmatism.

Successfully Governing Milwaukee

It was a challenging task, requiring constant wagers and adjustments, to pull the mass of working people toward socialism without undermining this process by jumping too far ahead. “Never swing to the right or too far to the left,” advised Daniel Hoan, the party’s mayor from 1916 through 1940. But concretizing this axiom into practical politics was easier said than done — especially once the party had to govern.

Given the powerful forces arrayed against them, and the unique obstacles facing radical politics in the US, the remarkable thing about the sewer socialist administrations is how much they achieved. Under SDP rule, Milwaukee dramatically improved health and safety conditions for its citizens in their neighborhoods as well as on the job. Milwaukee built up the country’s first public housing cooperative and it pioneered city planning through comprehensive zoning codes. And though the SDP did not advance as far as it wanted in ending private contracts for all utilities, it succeeded in building a city-owned power plant and municipalizing the stone quarry, street lighting, sewage disposal, and water purification.

Another crown jewel of sewer socialism was its dramatic expansion of parks and playgrounds, as well as its creation of over 40 social centers across Milwaukee. The city leaned on school infrastructure to set up these centers, which provided billiards for teens, education classes and public events for adults, plus sports, games and entertainment for all. “During working hours, we make a living and during leisure hours, we make a life,” was the motto coined by Dorothy Enderis, who headed the parks and recreation department after 1919.

The city’s excellent provision of recreation, services, and material relief was, according to Mayor Hoan, responsible for it having one of the lowest crime rates of any big city in the nation. In his fascinating 1936 book City Government: The Record of the Milwaukee Experiment, Hoan writes that in “Milwaukee we have held that crime prevention [via attacking its social roots] is as important, if not more so, if a comparison is possible, than crime detection and punishment.” Comparing the cost of policing to the cost of social services, Hoan estimated that the city saved over $1,200,000 yearly via its robust parks and recreation department. This did not mean Milwaukee ever considered defunding its police. Sewer socialists in fact pushed for better wages and working conditions for cops, in a relatively successful attempt to win away rank-and-file police from their reactionary chief John Janssen.

After the first significant migration of Black workers arrived in World War I, Mayor Hoan led a hard fight against the Ku Klux Klan in the city, while Victor Berger (breaking from his earlier white supremacism) led a parallel, high-profile fight in Congress against lynching as well as against immigration restrictions. As historian Joe Trotter notes, Milwaukee’s Black workers responded by consistently voting Socialist and leaders of the town’s Garveyite Universal Negro Improvement Association joined the SDP and agitated for its candidates.

Ending graft and promoting governmental efficiency was another major focus. One of the first steps taken by Emil Seidel, the party’s mayor from 1910 through 1912, was to set up a Bureau of Economy and Efficiency — the nation’s first, tasked with streamlining governance. Despite the protestations of some party members, Socialist administrations did not prioritize giving posts to SDP members. Mayor Hoan defended the merit system on anti-capitalist grounds: “You must show the working people and the citizens of the city that the city is as good as and better an employer than private industry if you are to gain headway in convincing them that the municipality is a better owner of the public utilities and industries than private corporations.”

Boosting the public’s confidence in governmental initiatives eventually made it possible for Mayor Hoan to push the limits of acceptability regarding city incursions into the free market. Before and following World War I, Hoan — without city council approval — purchased train carloads of surplus foods and clothing from the US Army and sold them to the public far below market prices at city offices. The project’s scope was ambitious: in January 1920 alone, Hoan purchased 72,000 cans of peas, 33,600 cans of baked beans, 100,000 pounds of salt, 20,000 pairs of knit gloves and wool socks, among other items. Basking in the project’s success, the mayor noted that “the public sale of food by me has offered an opportunity of demonstrating the Socialist theory of operating a business. It should demonstrate once and for all that the Socialist theory in conducting many of our enterprises without profits can be worked out in a grand and beneficial manner if handled by those who believe in its success.”

In contrast with progressive city administrations nationwide, Milwaukee socialists believed that effective governmental change depended to a large degree on bottom-up organizing. A sense of this can be gleaned from the Milwaukee Free Press’s story about the SDP’s rally the night it won the mayoral race in 1910:

A full ten minutes the crowd stood up on its feet and cheered for Victor Berger; waved flags and tossed hats high in the air; cried and shouted and even wept, for very overflowing of joy. Then Mr. Berger stepped forward, and a hush fell upon the audience as he began to speak. “I want to ask every man and woman in this audience to stand up here and now enter a solemn pledge to do everything in our power to help the men whom the people have chosen to fulfill their duty,” said Mr. Berger. Like a mighty wave of humanity, the crowd surged to its feet, and in a shout that shook the building and echoed down the street to the thousands who waited there, gave the required pledge.

Grassroots pressure became increasingly urgent once the party lost its short-lived control over the city council. Given Mayor Hoan’s lack of a majority, historian Todd Fulda notes that he chose to “take a populist approach to governing, appealing directly to the citizens of Milwaukee to support his reforms and pressure the non-partisan aldermen to support them as well.” The same strategy informed the party’s approach on a statewide level, leading the SDP to power-map the legislature to figure out pressure points to flip movable office-holders.

Socialist administrations also did everything possible to boost union power. Union labor was used on all city construction and printing projects. With city backing, a unionization wave swept the city’s firemen, garbage collectors, coal passers, and elevator operators, among others. Mayor Seidel even threatened to swear in striking workers as police deputies if the police chief attempted to intimidate strikers.

And in 1935 the SDP succeeded in passing America’s strongest labor law: the “Boncel Ordinance,” which empowered the city administration to close the plants of any company that refused to collectively bargain and whose refusal resulted in crowds of over 200 people two days in a row. Employers who refused to comply would be fined or imprisoned. With support from governmental policy above and workplace organizing below, Milwaukee County’s union density grew tenfold from 1929 through 1939. By the end of the 1930s roughly 60 percent of its workers were in unions. In contrast, New York City at its peak only reached a union density of at most 33 percent.

Demise

Despite labor’s upsurge and the SDP’s continued efforts to educate the public about socialism, the movement’s forward advance was significantly constrained by employer opposition and public opinion, which as ever was shaped by America’s uniquely challenging terrain, as well as media scaremongering and the normal, expectations-lowering pull of capitalist social relations.

By the late 1930s, backlash against union militancy and governmental radicalism had begun to take an electoral toll in Wisconsin and nationwide. Incensed by Mayor Hoan’s refusal to impose an austerity budget, employers had waged a “war” to recall him in 1933. Though they lost that battle, Milwaukee’s bourgeois establishment succeeded in convincing a majority of voters to defeat the SDP’s subsequent referendum to municipalize the electric utility. In 1940, Hoan decisively lost the mayoral race to a handsome but politically vacuous centrist named Carl Zeidler. Sewer socialism’s reign was over. (Another Socialist, Frank Zeidler, became mayor of Milwaukee from 1948 through 1960, but by this time the party was a shell of its former self.)

The central obstacle to moving further toward social democracy and socialism in America was simple: the organized Left and its allied unions were not powerful enough to convince a majority of people to actively support such an advance. This is a sobering fact to acknowledge, since it runs contrary to radicals’ longtime assumption that misleadership and cooptation are our primary obstacles to success.

But given the many structural challenges facing US leftism, the most remarkable thing about sewer socialism — and the broader New Deal that it helped pioneer — was not its limitations but rather its remarkable advances, which provided an unprecedented degree of economic security and workplace freedom to countless Americans.

Relevance for Today

The history of sewer socialism provides a roadmap for radicals today aiming to build a viable alternative to Trumpism and Democratic centrism. Milwaukee’s experience shows that the Left not only can govern, but that it can do so considerably more effectively than either establishment politicians or progressive solo operators. That’s the real reason why defenders of the status quo are so worried about a democratic socialist like Zohran Mamdani.

We have much to learn from Wisconsin’s successful efforts to root socialism in the American working class. Unlike uncompromising socialists to their left, the SDP consistently oriented its agitation to the broad mass of working people, rather than a small radicalized periphery; it combined union organizing and disruptive strikes with a hard-nosed focus on winning electoral contests and policy changes; it centered workers’ material needs; it made compromises when necessary; it based its tactics on concrete analyses of public opinion and the relationship of class forces rather than imported formulas or wishful thinking; it saw that fights for widely and deeply felt demands would do more than party propaganda to radicalize millions; and, eventually, it came to understand the need to balance political independence with broader alliances.

Today’s radicals would do well to adopt the basic political orientation of Berger’s current. But it would be contrary to the non-dogmatic spirit of the sewer socialists to try to simply copy and paste all of their tactics. Building a nationwide third party, for example, is not feasible in our contemporary context because of exceptionally high ideological polarization combined with the entrenchment of America’s unique party system over the past century.

As we search for the most effective ways to overcome an increasingly authoritarian and oligarchic status quo, on a terrain of widespread working-class atomization, it would serve us well to heed Berger’s reminder to his comrades: “We must learn a great deal.”

[This is a working paper, the final version of which will be a much longer essay for Catalyst, America’s best socialist journal. Subscribe today to Catalyst and you’ll get my upcoming piece as well as the magazine’s other excellent content. My final paper will take a deeper dive into all the topics touched on above, as well as other questions I didn’t have space here to address, such as the evolution of SDP electoral tactics, how it supported and disciplined its elected officials, its somewhat dogmatic approach initially to labor party and farmer movements, and tensions between grassroots mass organizing and Socialist administrations in Milwaukee.]

More

Starbucks workers are on strike, don’t buy anything from the company anywhere in the US until the strike is over!

It’s going to take each of us to rebuild a powerful Left and a powerful union movement. Join DSA. Unionize your workplace. Become a salt at a strategic company. Get involved in the fight to win Zohran’s agenda.

Here’s some more work of mine related to sewer socialism: an article on Oklahoma’s remarkable socialist movement; an article on the early rise of labor politics in Britain; and and article on how socialists should relate to the Democratic Party today.

Excellent piece! A shame they don't teach us about it, growing up in Milwaukee.

I've always been fascinated about those old socialist papers. Would you know any way of accessing them?

This piece is super insightful, clarifying so much and making me wonder what if todays Left could architect such deep union integration.