We’ve Had a Nationwide Immigrant Strike Before. We Can Do It Again.

The 2006 “Day Without an Immigrant” offers urgent lessons for beating ICE today

You don’t have to imagine what a nationwide strike in defense of immigrants could look like. It’s already happened.

Everyone looking to stop ICE today has a lot to learn from the explosive mass movement that culminated in the “Day Without an Immigrant” on May 1, 2006. The spark was H.R. 4437, the Sensenbrenner bill, which passed the House of Representatives on December 16, 2005. Sensenbrenner’s bill would have made it a felony for immigrants not to have papers, while also criminalizing acts of support and solidarity.

The threat was clear and the response spread fast. As one Los Angeles protest sign put it, “You’ve kicked a sleeping giant.” In the spring of 2006, between 4 and 5 million people marched in over 160 cities. And on May 1, over a million people walked out and poured into the streets across the country. Ports slowed; classrooms emptied; restaurants, shops, and job sites went short-staffed or dark. Chris Zamora, a marcher in Los Angeles, described what that collective power felt like on the ground: “It gives me chills to be a part of it. Thirty years from now, I’ll look back and say, ‘I was there.’”

The mass marches and economic disruption worked: Sensenbrenner’s bill was killed by the Senate in late May. It was a historic victory for the immigrant rights movement and the American working class.

History doesn’t repeat, but it is definitely rhyming a lot these days. Sensenbrenner’s nightmarish vision has become a reality under Trump. The good news is that today’s fights against ICE don’t have to reinvent the wheel—we just have to learn from the last time America’s immigrants flexed their power and came out on top. Here are some key lessons from the spring of 2006.

Let Youth Lead

Before May Day 2006 became a national work stoppage, the spark jumped where sparks often jump first: young people. Thousands of high school walkouts erupted across the country in late March, showing millions that non-violent disruption was possible.

Youth catalysis is a common pattern in social movements. But this dynamic is especially prominent among immigrants because children of undocumented parents more frequently have papers, more often speak English, and more often feel rooted enough to intervene in American politics. Unsurprisingly, one study found that over 51% of May Day participants were between the ages of 14 and 28. A century earlier, it was precisely this layer of second-generation immigrant youth that led the era’s mass strikes and unionization efforts during the Great Depression.

Young Latinos also took the lead in convincing their parents to join the spring 2006 actions. Señora Pacheco, an undocumented immigrant, recalled that she participated in one of the local marches—her first ever political action—after her 11-year-old U.S.-born son convinced her to attend. Similarly, one Chicago high schooler remembered the conversation he had with his parents on the eve of May 1: “I told them how me and my friends are going to go and, if they go, it would be better ’cause at least if one more person [goes], that can make a difference.” Initially “they weren’t that into it [but eventually] they were agreeing with me, then they started to talk to me about the other stories of how they worked.”

Working-class youth today remain the most important, and relatively untapped, conduit for organizing more broadly and deeply among working people against ICE and Trumpism. In fact, kids of immigrants are even more strategically central today than they were in 2006 because fears of speaking out are exponentially higher now. At a moment when undocumented parents are often justifiably scared to leave the house for weeks on end, the responsibility of their children to lead politically becomes even sharper.

We can already see glimpses of this potential. Though most young immigrants are not yet coming to our meetings or rallies, it’s significant that Zohran Mamdani got his strongest support among these demographics: 86% of young Latinos voted Zohran, 84% of young Black people, and 66% of young whites.

In Minneapolis, the first walkouts against ICE’s surge came on January 14, when thousands of St. Paul high school students walked out and converged on the state Capitol. And high school students were the only significant layer of the U.S. population to widely respond to the January 30 calls for a nationwide strike against ICE.

Connecting with and developing the organic leaders that initiated those walkouts is one of the key tasks for any anti-ICE movement that aspires to break beyond existing activists. (Left-leaning teachers should help connect walkout leaders to organizations willing to help them deepen their activism.) This means more than having token youth speakers at press conferences or non-profit board meetings; it requires providing resources and training to student leaders, involving young people in the decision-making of the broader fightback, and taking a cue from their more risky and disruptive inclinations.

Have Clear, Winnable Demands

Inexperienced activists sometimes think that raising more demands will broaden the movement by making sure everybody’s concerns are included. And radicals frequently double down on the most ambitious demands.

While the most appropriate number of demands is always context-specific, experience in 2006 and since shows that activating millions usually depends on centering a widely and deeply felt demand that’s also winnable. Laundry lists generally only appeal to the already-converted, and it’s hard to generate mass action around transformational policies that, however righteous, everyday people don’t think can be won anytime soon.

One reason the movement spread like wildfire in 2006 is that it was united around a clear, achievable demand: stop the Sensenbrenner bill. As PBS news coverage at the time noted, “That bill, known as H.R.-4437, has been the main point of protest for most demonstrators.” Those without financial cushions or immigration papers normally only take political risks in fights with a clear path to victory.

What’s our equivalent unifying demand today? If we want ordinary people to strike this year or 2028, what do we want them to strike for?

One initial difficulty organizing under Trump 2.0 was that his onslaught of attacks demoralized people (“what’s the point of protesting, he won’t listen”) and made it hard to focus mass attention around a particular fightback, since so many fires were burning at once. As such, the best we could do was No Kings marches and Fighting Oligarchy rallies that had a central slogan, but no unifying demands or concrete next-step campaigns.

But the horror of ICE’s siege has created a new dynamic, as seen in the January 23 strike concentrated around the demand “ICE Out of Minnesota.” Similarly, organizations like the Sunrise Movement have begun scaling up winnable campaigns to demand companies like Hilton break from ICE.

If we’re going to have a real nationwide mass strike in the U.S., it probably won’t be around a long list of demands or ambitious reforms like Abolish ICE or Medicare for All, policies that are more appropriate for a presidential platform. Rather, we should orient to seizing whirlwind moments to scale up mass non-violent disruption for immediate-but-winnable demands like “ICE Out of Cities” or “Respect Our Votes” after Trump tries to steal the election.

Media Matters

Getting to scale in 2006 came from a feedback loop between local organizing and a media “air war” that made people feel they were part of something bigger. Unions, community organizations, student groups, and assorted radicals played a key role in anchoring the movement.

But Spanish-language radio was a particularly decisive accelerant, with two nationally syndicated DJs, Renán Almendárez Coello (“El Cucuy”) and Eduardo Sotelo (“El Piolín”), playing a central role in promoting the fightback. This radio push didn’t happen “spontaneously.” As one account notes, “After organizers convinced the DJs that this was an important moment, immigration reform and the upcoming rally were constant topics on their shows.” A survey of marchers at the huge May 1 rally in Chicago found that just over half had heard about it on TV or radio.

This “air war” was paired with loose, fast coordination on the ground. Foreshadowing digitally enabled movements to come—with all their scalable strengths and long-term difficulties building sustained power—2006’s actions also went viral from below among young people via text messages, MySpace, and emails.

The problem now is that the media environment is far more atomized and Spanish-language media—recently taken over by finance capital—is much more hesitant to speak truth to power. In 2006, a few DJs could create shared rhythm across cities; today, attention fractures across feeds, group chats, and algorithms. Replicating that viral spread probably requires two things: first, movement organizations treating media strategy as core work—mapping the ecosystem, building repeatable content pipelines, and coordinating amplification rather than assuming it will happen organically; and second, the biggest platforms on the left—Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Zohran Mamdani—lending legitimacy and reach to campaigns that are already escalating on the ground.

This also means fights inside Spanish-language media organizations themselves. Their response to Trump’s horror show has been remarkably muted, reflecting the overall trend of corporate America to bend the knee to the new administration. Even before November 2024, the TelevisaUnivision leadership pushed positive high-profile coverage of Trump, prompting some Latino civic groups to publicly protest and demand changes. If 2006 proved what Spanish-language media can do when it acts like an organizer, the lesson for 2026 is that getting back to scale may require organizing the media.

Win the Normies

If you’re serious about building toward something like a general strike, you can’t just mobilize the already-convinced. You have to involve the mainstream masses, including people who don’t talk like activists or academics, who don’t follow movement Twitter, and who don’t want to feel like they’re joining a niche subculture fight.

The 2006 immigrant uprising learned that in real time, in part because opponents kept trying to frame immigrants as outsiders and criminals. Early on, that frame found openings. In Denver, marchers emphasized a familiar immigrant story—hard work, family, a better life—but the presence of Mexican flags and Spanish-language signs made it easier for anti-immigrant forces to paint protesters as “lawbreaking criminals unwilling to assimilate.” Organizers responded by sharpening a mainstream frame and a mainstream look: family, work, and belonging here.

After the March protests, a sea of American flags drowned out Mexican flags, not only in Colorado but across the nation. Rafael Tabares, a senior at Los Angeles’s Marshall High who helped plan that school’s March 24 walkout, insisted that his classmates “put away Mexican flags they had brought to the demonstration—predicting, correctly, that the flags would be shown on the news and that the demonstrators would be criticized as nationalists for other countries, not residents seeking rights at home.” This doesn’t mean everyone must perform American patriotism to deserve rights; last night’s beautiful Super Bowl halftime show by Bad Bunny showed how an expansive Pan-American vision can widely resonate in certain contexts and forms. But if you want your movement to win a majority, you have to think like a hardheaded organizer aiming at persuasion, not like an online poster fishing for likes.

Just as important was collective discipline, especially a conscious decision to avoid violence or property destruction. The marches were notable for having few arrests and virtually no acts of violence, and that mattered because mainstream coverage often scares off broad participation and sways public opinion by zooming in on the most chaotic image available, even when it’s peripheral.

Randy Shaw notes that in this respect 2006 differed from recent protests like the 1999 anti-WTO “Battle in Seattle” and the demonstrations at the 2004 Republican National Convention:

Although these demonstrations were primarily peaceful, media footage typically portrayed protesters battling police or engaging in conduct that detracted from their message. Activists often criticize the media for promoting such images, arguing that random acts are inevitable and cannot be controlled by event organizers. But such acts were absent from the immigrant rights marches of 2006.

If the goal is broad participation, you have to attract newcomers by making the action feel as safe and as collective as possible. Evelyn Flores, one of the student leaders, recalled that the sea of humanity she saw on May 1 spurred “the deepest emotions I have ever felt.” That feeling of collective power does far more to actually challenge the system than acts like vandalizing an ICE office or throwing a bottle at a cop.

Emilia González Avalos of Unidos MN put the question well on the Dig:

Are we disciplined enough? Are we disciplined enough to remain non-violent in a peaceful escalation that takes risks, that takes sacrifice, so that we can protect the normies that are coming and being onboarded, so that they feel that they have the courage to march in below zero degrees and not shop, not go to school, not use services for a day?

Answering that question strategically is the bridge from protest to shutdown: not just anger, but collective discipline that keeps the door open for millions more to join.

This also means involving mainstream institutions like churches—and 2006 shows why. The Catholic Church mattered not only because of its infrastructure and weekly contact with parishioners, but because it could legitimize protest in moral terms and pull participation into ritual life. In Los Angeles, Cardinal Roger Mahony announced that “if the Sensenbrenner bill was enacted and providing assistance to undocumented immigrants became a felony, he would instruct both priests and lay Catholics to break the law.” Sometimes it takes a preacher to help a movement move beyond preaching to the converted.

Mainstream outreach also brings real tactical dilemmas and debates. Church leadership and major unions pushed for after-work May Day rallies that minimized job conflict, attempting to steer people away from midday disruption. Mahony waged a very public and divisive push for students to stay in class and workers to stay on the job on May Day. Debates over these tactical questions were sharp and often bitter. But you can’t avoid those tensions if you want scale; you have to navigate them with the bigger goal in mind: building enough mainstream participation, legitimacy, and discipline that a broader shutdown becomes thinkable—and then doable.

Don’t Wait for Union Leaders to Call Strikes

Unions like SEIU and UNITE HERE played a key role across the country in providing staff and resources to make local marches a success. But the call for a “Gran Paro” (Mass Shutdown) on May 1 did not come from the unions. It came from Los Angeles’ community-based “March 25 Coalition,” which in early April called for a national boycott and work stoppage on May 1: “No Work, No School, No Sales, and No Buying.”

Unions discouraged their members from participating in the May Day walkouts, arguing that they risked losing their jobs and risked sparking unnecessary backlash against the movement. As such, in cities like Los Angeles and beyond organized labor took the lead in organizing late afternoon actions accessible to those who went to work.

The labor movement’s unwillingness to support the May 1 shutdown led one March 25 Coalition member to complain that “the last weapon the worker has against the employer is the strike, and the very institutions [unions] that live or die by the strike” actively opposed the push for one. “I think it’s shameful that the supposed leader [organized labor] of the working class in America was telling [immigrants] that they should behave” and not strike.

This type of labor-community split was fortunately avoided in Minnesota. Again, it was not union leaders who took the lead: community organizations called for the January 23 day of Truth and Freedom—with its call for “no work, no shopping, no school.” But unlike in 2006, Minnesota’s progressive unions immediately responded by endorsing the day of action. This didn’t mean they explicitly endorsed striking—a move that would have constituted an open defiance of labor law. But unions like SEIU Local 26 did not discourage their members from calling in sick for the day and their endorsement of the daytime rally gave it momentum and legitimacy. The result was a powerful social strike on the 23rd. There’s no reason other cities and other unions can’t replicate this playbook.

Towards a New Upsurge

Working-class advances in the U.S. don’t generally come through slow-but-steady rhythms. In most times and places, working people keep their heads down. Every so often, however, millions of everyday people suddenly force open the gates of the political arena. In such moments of upsurge, the impossible suddenly becomes possible.

The spring of 2006 was one such upsurge. So is today’s non-violent mass resistance against ICE in Minnesota. We can’t know when exactly such a nationwide upsurge will shake the United States again—or what exactly will trigger it—but we’re moving in that direction. The brazenness and unpopularity of Trump’s regime are a very explosive mix.

There’s no magic formula for awakening the sleeping giant. But ramping up our organizing today against ICE can hasten such a working-class upsurge and position us to seize it as fully as possible. And when that giant fully awakens, nothing can stop it.

More

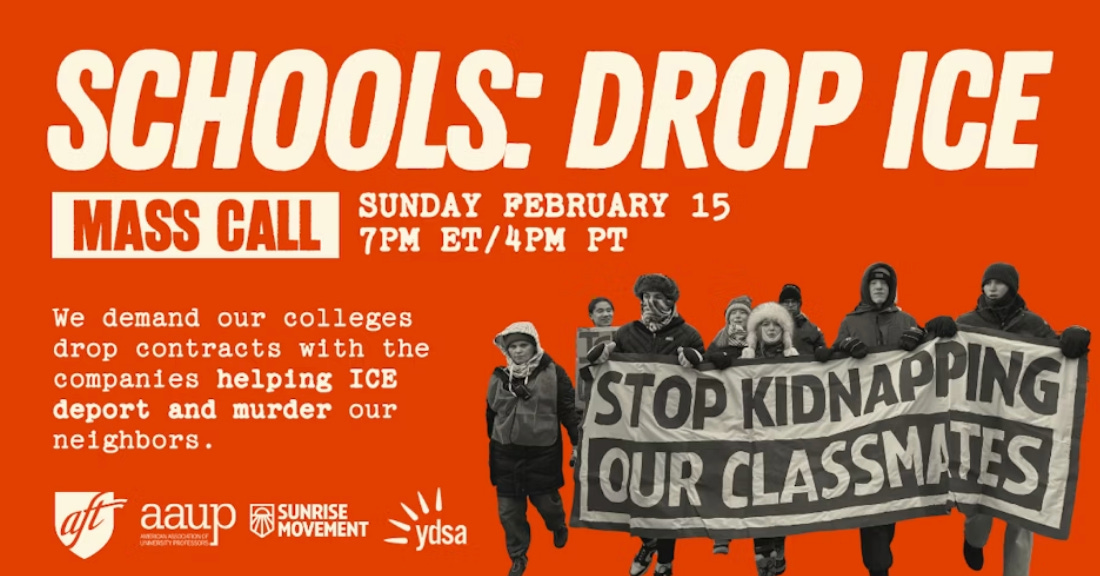

Join a nationwide mass call to launch campaigns on your campus to kick off ICE’s corporate collaborators. The call is this Sunday, February 15, at 7pm ET and is sponsored by the AFT, AAUP, Sunrise, and YDSA. You can sign up here.

Please share this article over social media and in your group chats! This free newsletter is a labor of love and depends on comrades like you to spread the word.

Do you work at a company collaborating with ICE? Reach out to the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee to get support organizing your co-workers to take a stand.

Democratic Socialists of America surpassed 100,000 members! Join today.

One thing the labour movement needs to think through is a strategy to consciously nurture an information ecosystem that doesn't allow the oligarchs to "flood the field with shit".