Liberals Get the New Deal Wrong

Why Voting is Not Enough

[This is the first installment in a four part series of new working papers, Labor Struggle from Below and Above: Lessons from the 1930s.]

For the first time in decades, labor organizing is front page news in the United States. Workers are in motion from Amazon to Starbucks, raising hopes that labor’s decades-long decline may finally be reversed. Faced with looming climate disasters, Supreme Court efforts to roll back democratic rights, as well as rampant economic and racial inequalities, there’s little time to lose.

To help seize the current moment, this four-part series takes a fresh look at labor and politics in the 1930s, an era during which an unprecedented number of U.S. workers joined unions.

How did workers during the Depression achieve their major breakthrough? Most pundits and unions today primarily credit organized labor’s successes in the 1930s to sympathetic government officials as well as changes in labor law. Along these lines, for decades, efforts to revive the labor movement have focused overwhelmingly on electoral politics. As former AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka explained in 2021, “FDR gave the U.S. a New Deal. The PRO Act is how we renew that deal.”

In contrast, the most influential radical explanation of this period credits bottom-up militancy and draws its strategic lessons accordingly. As Charlie Post argues, the 1930s demonstrates why “real gains for working people, people of color, women, LGBT, and immigrants are only won through mass social disruption—through strikes, demonstrations, occupations, and the like.” Though various labor historians have compellingly synthesized insights from both interpretations, much of the discussion has nevertheless tended to fall into dichotomous camps, from the widely-read debate between political scientists Michael Goldfield and Theda Skocpol three decades ago to Left polemics today.

Getting this history right has vital political stakes today. “History never repeats itself,” Mark Twain is purported to have said, “but it does often rhyme.” By leveraging new primary sources as well as secondary works, both published and unpublished, I show that it took a combination of workplace militancy and government-level political initiatives to bring about labor’s unprecedented wins. Both were essential — and neither were simply an effect of the other.

There is still much to learn and uncover from the history of labor during the Great Depression. It’s an experience full of lessons on how workers can turn the world upside down against seemingly insurmountable odds, on how unions can effectively relate to Democratic politicians, and on how the anti-democratic structures of the U.S. government — including the Supreme Court — can be overcome. This story suggests one big strategic takeaway in particular: scaling up working-class power requires struggle at work and pro-labor interventions in the political arena.

Politics and/or Protest?

The most widespread take on the 1930s is that union growth and the other progressive advances of this era were primarily produced by the initiatives of President Roosevelt and his New Deal administration. As one Bloomberg op-ed recently put it, “Biden’s support for unions … echoes FDR’s creation of the modern system of labor organizing.” Insofar as top union leaders discuss labor history, their analysis primarily credits FDR and their approach to labor renewal tends to be correspondingly electoral-focused.

A much more rigorous and historically-grounded version of this state-centric account was developed by eminent political scientist Theda Skocpol, who gives credit to other wings of state actors — particularly New York Senator Robert F. Wagner — rather than FDR himself. In her view, “New Deal labor insurgency was a response to public policy.” Specifically, Skocpol argues that labor’s turnaround in the 1930s came from two government-level initiatives.

First, large numbers of workers were inspired to organize by Section 7(a) — which proclaimed labor’s right to unionize — of the June 1933 legislation that founded the National Recovery Administration (NRA), the New Deal’s first major political initiative. Meant to end the depression through promoting industrial self-regulation, the NRA began a dramatic break with the federal government’s long-standing aversion to involving itself in labor relations, at least for any purposes other than smashing strikes. Though 7(a) ultimately frustrated workers’ expectations due to its lack of enforcement mechanisms over employers, Skocpol argues that it set into motion the period’s labor upsurge — and, by embroiling the government in industrial disputes, it constituted the first step in an epochal shift in governmental labor policy from repression to recognition.

Second, in the wake of the NRA’s evident failure to stabilize either the economy or workplace relations, Congress passed the forthrightly pro-union Wagner Act in 1935, which explicitly banned employer-created company unions, created a legal framework for collective bargaining, and established a robust federal apparatus to enforce the new system. Before this pivotal turning point, labor unions in the United States had never been able to get past a “boom and bust” pattern, in which union growth during an upsurge was quickly reversed by state-employer repression. (See Figure 1 to compare the post-WWI upsurge and that of the 1930s.) In short, Skocpol argues that the New Deal’s unprecedented policy changes emboldened workers to unionize — and ensured, for the first time in U.S. history, that their gains would last for generations.

Figure 1

U.S. Union Density, 1900-55

Much of Skocpol’s account is accurate and her work, at its best, has deepened our understanding of the relative autonomy of state actors and governmental politics. More specifically, she is right in stressing the importance of 7(a) and the Wagner Act, even if, as I argue below, she presents a one-sided explanation of their genesis.

Skocpol’s account is also closer to the historical record than liberal hagiographical takes on President Roosevelt, who she notes was hardly a consistent fighter for organized labor. On this, the evidence is clear: though FDR’s promise of a “New Deal” dramatically raised popular expectations, his 1932 election campaign said nothing about union rights and his new Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, was an advocate of wage and hour regulations, not collective bargaining.

Section 7(a) was not an FDR initiative; the fact that it ended up playing such a major role in reviving trade unionism was unexpected and largely undesired for the new administration. During his first two years in office, Roosevelt generally undermined efforts to establish robust federal enforcement for union rights and in 1935 he only acceded to the Wagner Act at the very last minute once it became clear it would pass Congress with or without his blessing.

FDR’s honeymoon with industrial unionism was consequential, but it only lasted from 1935 through 1937. Once the tide of public opinion began to turn in the wake of the controversial 1937 Flint sit-down strike, FDR did not hesitate to distance himself from the militant Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). He proved to be, at best, a fair-weather friend, as did Democratic politicians generally.

From the summer of 1937 onwards, as historian Melvyn Dubofsky notes, Roosevelt “retreated from his firm support of CIO and mass-production unionism and maneuvered to free himself from the quagmire of labor-capital conflict.” After FDR declared “a plague on both your houses” during the violent “Little Steel” strike of mid-1937, CIO president John L. Lewis replied in a national radio broadcast that it “ill behooves one who has supped at labor's table and who has been sheltered in labor's house to curse with equal fervor and fine impartiality both labor and its adversaries when they become locked in deadly embrace.”

The Impact of Strikes

Skocpol, to her credit, avoids the still widespread lionization of Roosevelt. Yet her account fails to sufficiently acknowledge the decisive impact of bottom-up labor militancy, as manifest in work stoppages and in combative unionization drives. Neither 7(a) nor the 1935 passage of the Wagner Act, on their own, were sufficient for labor’s rise.

Numerous pieces of evidence undermine her account. First, Skocpol fails to note that there was a modest uptick in strike activity in 1931 and 1932, which suggests that while 7(a) boosted workers’ militancy from mid-1933 onwards, it did not create a labor upsurge from scratch (Figure 2). Nor does Skocpol acknowledge that most labor leaders initially failed to effectively leverage the excitement for new organizing generated by 7(a). Like the labor movement today, the craft union heads of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1933-34 were generally risk-averse and thereby sought to win unionization without work stoppages, relying instead on employer good will and the NRA’s newly set up mediation apparatuses.

Figure 2

U.S. Workers Involved in Strikes, 1925-1937

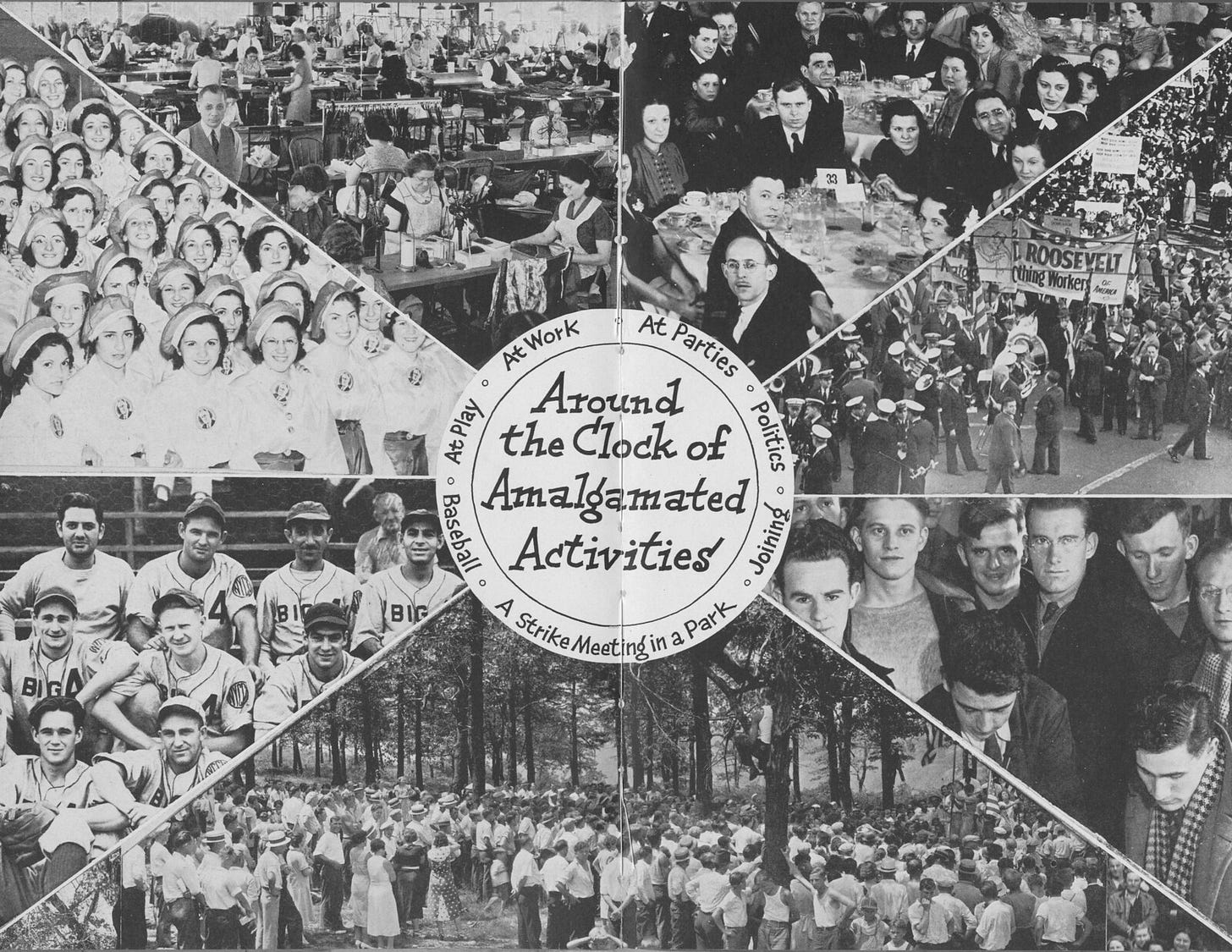

Against the AFL’s milquetoast approach, United Mine Workers (UMW) president John L. Lewis insisted that 7(a) and that NRA’s newly formed policies for recognizing unions would be “absolutely meaningless” unless they were “boldly and audaciously used as the weapon for a great organizational attack.” Though he would years later become an adjunct of the FDR administration, Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers (ACW) similarly insisted at a 1934 rally of 5,000 workers that “there are too many members in the organized labor movement, as well as leaders, who ought to have known better than to expect the government to hand over the mass of unorganized workers into the labor unions … The greatest battles are still ahead of us, and not behind us.”

Lewis and Hillman — as well as radical labor organizers to their left — were proven right on this score, as illustrated negatively by the defeats of the AFL leadership’s bungled, strike-averse attempts to unionize auto, steel, electrical, and metal mining. The biographer of AFL president William Green notes that his “failure to organize mass-production industries between 1933 and 1935” was primarily due to the fact that “he refused to abandon his moralistic approach [of voluntary class collaboration] even after it had proven itself bankrupt.”

Unlike in those minority of hyper-competitive industries such as garment and trucking where unions promised to potentially benefit companies by regulating industrial competition and preventing cost-cutting, bosses in mass production industries proved exceedingly unwilling to heed the calls of moderate labor leaders and state officials to peacefully cooperate with organized workers.

Even in the competition-heavy industries where companies were generally less stridently anti-union, strikes proved to be necessary for big advances after 7(a). The membership gains of CIO forerunners — such as the UMW and the ACW — demonstrated through positive example the effectiveness of class struggle, which was especially decisive in these years since the government did not yet have any mechanisms to force employers to respect 7(a). The same lesson was made even clearer in the victorious radical-led mass strikes of 1934 in Toledo, Minneapolis, and San Francisco.

As one 1935 scholarly investigation of labor under the NRA concluded, “those [unions] which have made substantial gains in membership have been those which depended upon the strike instead of government mediation to win their demands.” Skocpol’s one-sided argument that “New Deal labor insurgency was a response to public policy” unjustifiably ignores the consequential strategic choices and political clashes within organized labor in this period. Decisions and initiatives from below did matter.

Work stoppages in the second half of 1933 and especially in the spring and summer of 1934, in turn, played a major role in the implosion of the NRA, which employers abandoned once it became clear that it was boosting rather dampening industrial militancy and unionization. Skocpol rightly stresses that the NRA’s downfall was crucial for leading to the Wagner Act in 1935.

But by blaming this demise solely on the federal government’s low degree of state capacity, she ignores the centrality of labor strife in bringing down the NRA and giving birth to a robust, pro-labor bill. Already by October 1933, Henry Harriman of U.S. Chamber of Commerce was writing to FDR that a reaction against the NRA was emerging “among certain very large groups of businessmen,” who were “very greatly disturbed at strikes, at the unwarranted statements [regarding the meaning of Section 7(a)] being put out by local labor leaders and by the general unrest thereby created.”

By 1934, labor’s insurgency was front-page news, creating a crisis for both employers and politicians, as workers battled in the streets with strike breakers and local police forces. That year alone, over 40 workers were killed in strikes (Figure 3). All this created intense pressure on politicians to act. “Wagner Bill Advanced by Industrial Conflict,” declared a New York Times headline in May.

Figure 3

U.S. Strike Fatalities

Without this explosion of worker militancy, Wagner and his small cohort of legislative allies would not likely have found the votes in Congress to pass a sweeping, pro-union bill in 1935. As Goldfield has demonstrated, references to these strikes loomed large during the Act’s congressional hearings.

Moreover, the Wagner Act — like 7(a) before it — was ignored by large numbers of employers for the first two years of its existence. It did not truly become the recognized law of the land until April 1937 when, to the dismay and surprise of employers, the Supreme Court deemed it to be constitutional. And the single most important unionization breakthrough of the 1930s — the Flint sit-down strike, which broke the dam in auto — was won in February 1937, a month before the Wagner Act was ratified by Supreme Court justices. The decision of the Court itself appears to have been highly impacted by the strike upsurge engulfing the country. These non-legislative dynamics help explain why national union growth skyrocketed in 1937, not 1935 or 1933 (Figure 1).

Conclusion

Liberal accounts of the 1930s are irreparably one-sided and serve poorly as guides to action today. Faced with a Supreme Court rapidly undermining decades of advance, we urgently need mass disruption and unruly protest, especially from organized workers.

Unlike most unions’ prevailing kids-gloves approach thus far towards Joe Biden and a Democratic Congress, Depression-era labor leaders such as Lewis did not content themselves in the mid-1930s with electoral campaigning and backroom negotiations with the White House. They did initiate such efforts on an unprecedented scale. But the CIO, especially its radical Left flank, backed this politicking up with mass strikes and strategic unionization drives, which were essential for shifting the relationship of class forces sufficiently to win initial union victories and to bring labor reform to the legislative fore despite FDR’s equivocations, most employers’ obstinate refusal to bargain, and the U.S. government’s anti-democratic institutional blockages such as the Supreme Court.

In an account that compellingly stresses the agency of Wagner’s team and of insurgent workers, political scientist David Plotke notes that “labor's mobilization was crucial” for getting the legislation signed. Pro-union legislation and labor friendly politicians did not have the power to single-handedly create popular insurgencies, let alone to overcome corporate America’s intense opposition to unionization. This insight, unfortunately, became less and less of a strategic north star for labor after the 1930s. One of the tragedies of the U.S. union movement is that for a combination of objective and subjective factors, even formerly militant leaders like Sidney Hillman eventually lost their independence and subordinated themselves to a Democratic establishment that was unwilling to consistently champion their cause.

Labor’s repeated efforts to lobby its way back into sustained growth have failed since at least the 1960s. Yet despite this track record unions to this day remain stubbornly risk averse. As bold young workers, largely on their own initiative, in Starbucks, Amazon, and beyond are reviving the chances for labor to turn around its decades-long decline, unions generally remain missing-in-action when it comes to big, bold attempts to organize the unorganized. Even on narrow electoral grounds, a deference to Democratic politicians has proven ineffective: labor’s failure to take any serious bottom-up initiatives to push Biden to fulfill his campaign promises for transformational change is one of the reasons why the Republicans are frighteningly poised to sweep back into power.

To be sure, there are no silver bullets for labor success in a context as unfavorable to unions as the contemporary United States. And the decline of trade unions in all industrialized countries over the past decades suggests how deeply economic transformations have undermined organized labor. But insofar as labor’s crisis is self-induced, union conservatism remains by far the biggest culprit.

Challenging state-centric histories of the New Deal won’t on its own turn things around for working people. But understanding the real lessons of the 1930s can help contribute to today’s efforts to bring back the bottom-up militancy that is necessary, if not sufficient, for millions of workers to win again — and to stave off a further descent into minority rule.

[This is a working paper — republication without author’s consent is prohibited. Footnotes and sources available upon request.]

Greetings!

I'd be very grateful for a link to footnotes and resources.

Thank you,

Jonathan - educator in Oregon

JonathanPChenjeri@gmail.com

This is excellent and is basically what I have been teaching and organizing around for years. See the chapter on the law in our new book, "Power Despite Precarity" (with Helena Worthen, 2021, Pluto). I hope this article will be widely used and discussed. I hope future pieces will look at the rise of public sector (and some service sectors like health care ) unionism in the 60's and 70's through the same lens. Eric Blanc is on his way to becoming a movement treasure.

In solidarity,

Joe Berry