Class Politics Beyond the Blue-Collar?

Maisano Replies to Karp on “Class Dealignment”

How have deep structural transformations changed the present and future of Left politics? This is the pivotal question that Chris Maisano tackles in this special guest article, in which he replies to Matt Karp’s criticism of his case that today’s partisan voting patterns are far less decoupled from social class than is commonly believed.

Continuing the “Class Dealignment” Debate - A Reply to Matt Karp

Chris Maisano

I recently wrote an article for Jacobin that questions some of the main premises of the “class dealignment” view of US politics. Matt Karp, one of the leading exponents of that view, responded to my piece with an article of his own. Karp’s central contention is that class dealignment is “visible everywhere,” and that the argument I made pretends that this is a problem that doesn’t exist.

I appreciate Karp’s engagement with my argument. These are important questions for the left, and the more discussion and debate we have about them, the better. As I noted in my original piece, it is true that Republicans have made inroads among certain sections of the working class, white blue-collar workers without college degrees in particular, while voters with college degrees are solidifying their alignment with the Democrats. But is this evidence of a comprehensive shift, whether completed or ongoing, of working-class voters from the Democrats to the Republicans? This is where I am skeptical.

In my view, the class dealignment argument as it’s been elaborated suffers from some basic flaws. First, it tends to conflate educational attainment with class location. Second, it tends to conflate the blue-collar, industrial working class with the working class per se. Third, it tends to overlook or gloss over the massive erosion of industrial employment and the growth of new, highly-educated sections of the working class that barely existed in the mid-twentieth century, sections it tends to assign to an ill-defined “professional-managerial class.”

What I hope to show here is that the dealignment of lower-income and working-class voters away from the Democratic Party is often overstated; that the erosion of blue-collar industrial employment and the growth of highly-educated sections of the working class needs to be reflected in our political strategies; and that there is not a necessary contradiction between tending to the new left’s emergent base and appealing to other sections of the working class.

This may seem like a purely academic debate, but these aren’t just questions of interpretation. They have significant implications for left-wing politics and strategy, so it is important that we get as close to an accurate analysis of these dynamics as possible.

Interpreting Recent Election Data

Karp concedes that “a thin majority of lower-income voters is still Democratic” and that many higher earners are still Republicans. The Democratic advantage among lower-income voters, however, is often not particularly thin, particularly when we shift our attention from national-level election data to the states.

Biden beat Trump by a 9-point margin among voters with household incomes below $50,000 nationally. That is fairly large by today's standards, as presidential landslides of the 1936, 1964, or 1972 varieties don’t happen anymore. Yes, Biden won by a 13-point margin among voters with household incomes above $100,000 nationally, which I noted in my piece. There's no doubt that a substantial portion of those voters are people who are not ever going to be sympathetic to a left-wing agenda. But it is likely that this also includes plenty of voters from high-income/high cost-of-living states like California and New York where two working-class parents can combine for a family income over $100,000. Indeed, Biden won about 20% of his roughly 81 million popular votes from these two high-income states alone. It would be useful to investigate the composition of those voters to get a better sense of what they look like at a more finely-grained level. In doing so, we may find that many of them may not be reasonably described as elites at all.

Another point to note is that the composition of Trump’s 2020 voters was markedly less low-income than it was in 2016. According to data from Pew Research Center, in 2016, 43 percent of Trump’s voters had household incomes below $50,000; in 2020 it dropped 10 points to 33 percent. By contrast, low-income voters accounted for 37 percent of Biden’s voters, while an additional 32 percent fell in the $50,000-$99,999 range. 23 percent of Trump’s 2020 voters had incomes above $100,000, while 27% of Biden’s voters did. That’s not a major difference, and it likely reflects (at least in part) the fact that Democrats tend to be stronger in higher-income states while the GOP is stronger in lower-income states.

Moreover, Democratic candidates did quite well among lower-income voters in a number of high profile statewide races in the 2022 midterm elections. Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer trounced her Republican opponent by 18 points (58-40) among voters below $50,000; Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro beat his GOP opponent by a similar margin (57-41) in the same income group; Arizona governor Katie Hobbs lost to Republican Kari Lake by two points among voters over $50,000 but won by seven points among voters under that line; Arizona senator Mark Kelly tied Republican Blake Masters among higher-income voters but beat him 55-42 among lower-income voters; Pennsylvania senator John Fetterman beat Mehmet Oz by the same 13-point margin among lower-income voters, but only by 1 point among higher-income voters. These are not thin margins, and in the case of Katie Hobbs lower-income voters provided her with the margin she needed to squeeze out an extremely narrow win.

It is true that Republican candidates fared much better among lower-income voters in other races, particularly in states where the GOP enjoys a clear partisan advantage. Florida is one of the best examples of this, where governor Ron DeSantis beat his Democratic opponent 59-40 among all voters, and by the same 19-point margin among voters below the $50,000 line. What this helps to demonstrate is that voting behavior can and does vary dramatically from state to state. In states where Democrats are strong they tend to do well with many groups in the electorate, including low-income voters. The same goes for Republicans. The paradox of political nationalization is that it generates sharp divergences between states, which makes it very important to attend to electoral dynamics at this level.

Indeed, this comes through in state-level data from the 2020 presidential election. Biden trounced Trump among low-income voters in states like California (69-29), Illinois (61-37), Maryland (68-30), Massachusetts (68-30), New Jersey (63-36), New York (66-33), Virginia (58-40), and Washington (58-39). Biden also beat Trump among low-income voters in some important states he lost, including Florida (51-48) and Texas (51-47), but was swamped by big Trump margins among higher-income voters (41-58 in both states). And in the states that decided the election, Biden’s relative strength among low-income voters was key to building the margins he needed to win: Arizona (52-47), Georgia (52-46), Michigan (56-43), Nevada (57-40), Pennsylvania (52-47), and Wisconsin (55-43). Biden lost to Trump among voters with household incomes above $50,000 in all six of these states.

Democrats continue to do well among lower-income voters, particularly in the states where they are competitive or enjoy a consistent partisan advantage over Republicans. Focusing on national-level election data can miss these dynamics and lead to partial or misleading political conclusions.

The Blue-Collar Workforce has Shrunk Dramatically

Class dealignment arguments tend to overlook one of the most important structural processes of the last few decades: the enormous erosion of industrial and blue-collar employment, and the concomitant increase in managerial, professional, and service employment.

In his article, Karp argues that the social base of today’s left and center-left is “far smaller, weaker, and less united than the organized industrial workers of the twentieth century.” It is certainly true that organized industrial workers packed a potent political punch. As I noted in a 2019 Jacobin article, “industrial workers have historically been able to combine disruptive potential with organizational capacity in ways that other sections of the working class have typically not been able to.” They formed the vanguard of democratic and left-wing movements across the world, and powered many of the key victories working people won in the last century.

Karp is right that some blue-collar workers, particularly but not exclusively whites, have shifted their partisan allegiances from the Democrats to the Republicans. This is not in question; an array of data shows this; and it is a problem that both Democrats and the socialist left need to grapple with. At the same time, however, the size and social weight of this section of the working class has shrunk enormously since the mid-twentieth century. This is a major development that, in my view, the class dealignment view does not adequately deal with.

The chart below demonstrates the long-term erosion of manufacturing employment in the United States. Manufacturing’s share of employment reached nearly 40 percent in the 1940s, and has been dropping continuously ever since. Today, manufacturing employment stands at just about 8 percent; mining and logging, two industries at the vanguard of radical labor militancy in the twentieth century, dropped from around 3 percent to less than half a percentage point; construction stands at its rough historical average of about 5 percent.

At the same time, the share of workers in private service-providing industries and government employment has expanded to roughly 85 percent of the entire US workforce, as shown in the chart below:

As researchers from the St. Louis Federal Reserve note, these kinds of workers already accounted for roughly half the workforce as early as the late 1930s, and they have only increased since then. The US is second in the world in terms of manufacturing output behind China, but when it comes to employment shares “the emphasis is now on education, health, leisure, retail, information, and finance.”

Census Bureau data on employment by occupation underscores this point. 43 percent of employed civilians are now in professional, managerial, and related occupations, while another 19.2 percent are in sales and office occupations. Together, that's nearly 100 million people. Meanwhile, combining everyone in construction, extraction, production, transportation and materials moving occupations yields roughly 20 percent of employment, which translates to roughly 34 million people. To be more specific, there are now more people employed as healthcare practitioners and techs (9.8 million) than there are in construction and extraction (8.4 million) or production (8.2 million).

The explosion in educational attainment I highlighted in my original article is intimately related to these seismic shifts in the employment structure. These changes have, in turn, altered the relative shares of various income and education groups in the US electorate. In their 2019 paper on shifting partisan dynamics among white US voters, Herbert Kitschelt and Philipp Rehm calculate that the share of high-education/low-income voters in the white electorate - the “new working class” that has become the core social base of the left across the capitalist countries - has grown from next to nothing in the mid-twentieth century to roughly 15-20% today. At the same time, the low-income/low-education group has declined from roughly 50-60% in the 1950s down to the high 30s.

Karp focuses on the low-education/low-income (LE-LI) and high-education/high-income (HE-HI) groups to bolster his case. Again, it is true that a section of low-income/low-education voters have shifted to the GOP column. It is also true that many high-education/high-income voters have shifted to the Democratic column, particularly in urban and suburban areas. Noting those shifts without also noting these groups’ changing shares of the electorate, however, can lead to interpretive and strategic confusion.

According to Kitschelt and Rehm’s calculations, the LE-LI and HE-HI groups accounted for nearly 70 percent of the electorate in 1956. The low-education/low-income group (LE-LI) alone accounted for 60.5 percent, making it easily the largest of the four groups. Since then, however, the relative shares of all four groups have changed substantially. By 2016, LE-LI voters accounted for 37.7 percent, while the share of high-education/high-income (HE-HI) voters rose from around 6-7 percent to 26 percent. Meanwhile, the low-education/high-income (LE-HI) group declined from around 30 percent of the electorate to 22 percent, while the high-education/low-income (HE-LI) group spiked from 1-2 percent to around 15-16 percent. In this context, even if a Democratic presidential candidate won a clear majority of LE-LI voters it would not get them anywhere near a victory. They would still have to find substantial levels of support from voters in other groups to win an election.

One might look at this data and conclude that since the LE-LI group is still the biggest in the white electorate, and since HE-LI voters in particular are already disposed toward the left, strategic emphasis should be placed on winning as much of the LE-LI vote as possible. But the direction of change for this group is clear, and it points sharply downward - as it has for decades. The LE-HI group is also declining, but from a lower height and at a slower rate. At the same time, the arrow points clearly upward for both the HE-LI and HE-HI groups, raising the possibility of a rough convergence in the size of the four groups in the relatively near future. When thinking through the strategic implications of this trend, it’s important to remember that neither the lower-education nor the lower-income groups are the only ones with working-class voters in it. A cashier in the LE-LI group is certainly in the working class, but so is a social worker in the HE-LI group or a registered nurse in the HE-HI group. A strategic analysis that doesn’t adequately register these substantial changes in class composition or the likely impacts of cohort change runs the risk of proposing a counterproductive course of action.

Simply put, we are not dealing with the same employment structure, working class, or electorate from the “golden age” of twentieth century industrial capitalism. Karp is right to ask whether a motley crew of professional, service, and white-collar workers can pack the same punch as an organized mass of industrial workers. It may not be able to. But the industrial workforce has, like the agricultural workforce before it, shrunk enormously in both size and social weight. It can no longer be the tip of the spear, politically speaking, and the advance of labor-saving technology means that it probably cannot grow much larger than it currently is. Class dealignment arguments tend to overlook these developments or acknowledge them in passing, but they are key to understanding the shape of political competition as well as the limits and possibilities of various electoral strategies.

Is Lee County, Iowa a Strategic Priority?

Karp points to counties with low or moderate median household incomes that have shifted sharply Republican in recent election cycles to bolster his case for class dealignment. One of them is Lee County, Iowa. In 2008, Barack Obama won Lee County with nearly 60 percent of the vote. In 2020 those results flipped, and Donald Trump won it by roughly the same margin. That is striking, and it is symptomatic of the shifting partisan loyalties of small-town and rural areas around the country.

To Karp, winning over more voters in places like Lee County should be a strategic priority for both Democrats and the left. A closer look at Lee County’s economic and demographic data, however, suggests a healthy dose of pessimism in this regard.

In 2021, Lee County had roughly 33,000 residents. Its population has declined by roughly 25 percent since the 1970s, and the trajectory points further downward. Its number of private business establishments has gone down, as has its number of employed persons. As such, the county’s population has become quite elderly. It has the same proportion of residents aged 65 or older (21.4 percent) as it does persons under 18 years. It’s old compared to the rest of the country (16 percent of all Americans are 65+), and it’s old even by Iowa standards (17.7 percent statewide). Its homeownership rate is nearly 80 percent, markedly higher than the national rate of about 66 percent. Its poverty rate is higher than the state and national rates, but not by much, and its unemployment rate is similar to state and national rates too. The same goes for its proportion of residents on SNAP benefits. It is nearly 95 percent white, and it has a higher proportion of military veterans (6.7 percent) than foreign-born residents (1.6 percent).

Based on these numbers, Lee County appears to be a shrinking place with lots of older, retired, white, native-born homeowners. It has probably seen better times, but it is not McDowell County, West Virginia, a largely white and heavily Trump-voting county where the poverty rate is over 30 percent. There are lots of places like this in the US today, and Republicans tend to do pretty well in them. Lee County should not be condemned to an eternity in Hillary Clinton’s “basket of deplorables,” but is this promising ground for mainstream Democrats, much less the socialist left? It doesn’t seem like it.

Places like Lee County need to be on the radar of Democratic candidates for statewide office. They can run up numbers in cities and many suburbs with ease, but Republicans can beat them if the GOP candidate wins big enough margins in a lot of small places. Can a Democratic candidate for statewide office win majorities in places like Lee County? At this point, probably not. But they can limit their losses, and this is often key to victory. Compare John Fetterman’s margins in places like Butler County in western Pennsylvania to Hillary Clinton’s and you’ll get a clearer sense of why he won and she didn’t. Fetterman still got waxed in Butler County (36-61), but he won seven more points against Oz there than Clinton did against Trump (29-66). Add that up across a number of rural and small-town counties, combine it with huge margins from the vote-rich cities and surrounding areas, and you stand a good chance of winning.

It’s a different story for the left. Simply put, a socialist movement isn’t going anywhere in the Lee Counties of the world, at least for the foreseeable future. Sociology is not destiny, but the statistical profile sketched above paints a forbidding picture. It also gives us a sense of how non-college support for the GOP - one of the linchpins of the class dealignment view - is, at least in part, an artifact of age. Lee County is old, and its rate of bachelor’s degree holders - just 19.2 percent - is far below the national and state rates. Further investigation is necessary to confirm this, but it is probably safe to wager that the county’s electorate is heavily weighted toward older voters with no more than a high school diploma, or maybe some college but no degree. As this generation passes away, it will be interesting to see how this affects the non-college share of GOP voters over time, not just in Lee County but around the country.

Like It or Not

In this and in my original article, I have demonstrated three main points. First, Democrats continue to do well among low-income and working-class voters, particularly in the states where they are competitive or enjoy a consistent partisan advantage over Republicans. Second, it is a mistake to conflate educational attainment with class location, or the blue-collar working class with the working class per se. Finally, left-wing political strategy needs to proceed from the key structural developments of the last seventy years: the massive erosion of industrial employment, the explosion of higher education, and the growth of new sections of the working class that barely existed in the mid-twentieth century.

One area for further investigation is the geographical redistribution of industrial employment, and how this may have affected the partisan alignments of white blue-collar workers in particular. Industrial employment in the US hasn’t just shrunk since the mid-twentieth century. At the same time, much of what remained moved to the South, where white voters were realigning their partisan allegiances from the reactionary Bourbon Democracy to an increasingly reactionary Republican Party. By 2017, the manufacturing share of employment was higher in Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee than it was in California, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and every New England state. Manufacturing’s shift from political geographies where Democrats predominate to the Republican South - where cross-class mediating institutions like churches have always been far stronger than specifically working-class institutions like unions - is surely not the whole story, but it is fair to speculate whether this may have had a meaningful impact on the relative share of blue-collar workers voting GOP.

The class dealignment perspective gets at something important about contemporary politics. But its analytical and strategic purchase is limited because it doesn’t, in my view, adequately survey the social terrain of post-industrial capitalism. It also tends to suggest that there is an inherent tradeoff between winning the so-called professional-managerial class and winning working-class people to the left, when there isn’t. Many “PMCs” are actually working-class, and a growing body of research shows their political views are often strongly pro-labor and pro-redistribution. Political scientists Tarik Abou-Chadi and Simon Hix, for example, turn Thomas Piketty’s conception of the “Brahmin Left” on its head: “rather than assuming that the reason the left appeals to higher-educated voters is because center-left parties no longer support redistribution, our evidence suggests that those higher-educated voters who support the left do so because they support redistribution.” (emphasis in original)

In this connection, it’s worth noting that some of the most dynamic labor organizing happening in the US today is precisely among highly-educated workers. This suggests that the left’s electoral base in this group is not the result of a turn away from working-class politics, but because these are often the most militant sections of the working class today. Something like this was also true in the past. Early labor movements were often led by proletarianized artisans and the most highly skilled workers in industrial production. It may seem outlandish to compare baristas or programmers to early-twentieth century machinists, but the fact remains that these kinds of working people are often at the forefront of left-wing labor and political action today.

In his essay “Dysfunctional Democracies,” Göran Therborn says that “Politics is never reducible to sociology, but the latter may give useful hints of the limitations and potentials of the former.” The class dealignment view approaches US politics through a materialist lens, but it nonetheless tends to downplay the structural framework that shapes contemporary political competition - above all, the massive erosion of industrial employment and the growth of new sections of the working class. Whether we like it or not, the twenty-first century left and its social bases are different from earlier iterations. We need to accept this and formulate our political strategies accordingly.

Update: In both of my articles on class dealignment I rely heavily on Herbert Kitschelt’s and Philipp Rehm’s key 2019 paper, “Secular Partisan Realignment in the United States: The Socioeconomic Reconfiguration of White Partisan Support since the New Deal Era,” for evidence of the changing shares of various income and education groups in the US electorate and workforce. It is a rich source of data and analysis regarding many of the big questions that have vexed the new left since its recent emergence on the US political scene. I want to take a moment here to highlight one bit of data from the Kitschelt and Rehm paper that I did not in either of the two pieces, because I think it helps to shed even more light on the changing composition of the occupational structure in the US and its implications for the left.

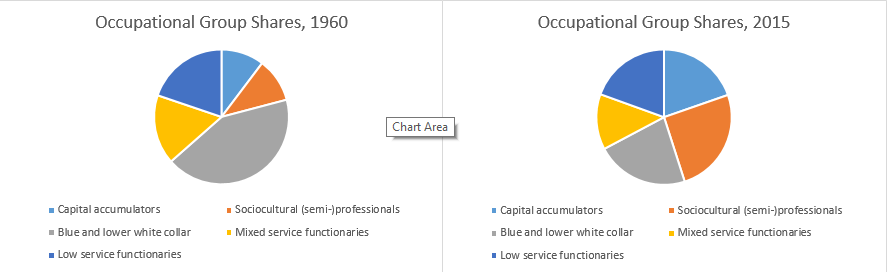

Deep in Appendix E, Kitschelt and Rehm present a table comparing the size and composition of various income and education groups based on Census Bureau data. They use that data to construct five large occupational groups in the US workforce: capital accumulators, sociocultural (semi-)professionals, blue and lower white collar workers, mixed service functionaries, and low service functionaries, and observe their sizes in 1960 and 2015. The table below shows that data in a more readable format, and adds in the rate of change for each occupational group over time:

Source: Kitschelt and Rehm (2019), p. 469

As the table makes clear, there has been a significant recomposition of the US workforce since the mid-twentieth century, defined by a shift away from routine blue and white collar work that does not require high levels of formal education, toward forms of work that are professional, managerial, or technical in nature and which require high levels of formal education. Indeed, the occupational group with the biggest rate of change is sociocultural (semi-) professionals, the group that is driving the growth of the new left in the US and other capitalist democracies. According to these calculations, it grew by nearly 140 percent since 1960 and is now the single largest occupational group in the US workforce. The group that shrunk the most was blue and lower white collar workers, which dropped by nearly half during this period. It is now the second largest group according to this data, behind sociocultural (semi-)professionals (educational, health, legal, social, and cultural professionals) and just above capital accumulators (higher-level business managers and administrators, scientists, engineers, and IT technicians).

This shift in occupational composition comes through even more clearly when you put the data into simple pie charts. As you can see below, in 1960 the blue and lower white collar group (the dark gray wedge) was easily the single largest occupational group, while capital accumulators and sociocultural (semi-)professionals were the smallest. By 2015, the various slices of the pie had become far more uniform in size. Sociocultural (semi-)professionals (the burnt orange wedge) grew significantly, taking up a big chunk of the pie that formerly belonged to blue and lower white collar workers.

Source: Kitschelt and Rehm (2019), p. 469

Legend has it that when the bank robber Willie Sutton was asked why he robbed banks, he said “because that’s where the money is.” The new left is growing where the growth is, and that’s a good thing. The fact that its main social base is, according to these calculations, in the single largest (and still growing) occupational group in the US should be a cause for optimism, not consternation.

This is not to say that all is well, and the new left just has to ride the wave of structural change to political power. Not at all. For one thing, the capital accumulators group has also grown substantially, nearly doubling in size since the mid-twentieth century. A growing proportion of this group is voting for Democrats, particularly in the big metropolitan areas, and this poses potential problems for a left-wing political project that uses Democratic Party primary elections as its main electoral vehicle. Expect continued, likely intensified, intra-party conflict in primaries and legislatures between pro-labor and pro-redistribution forces on the left, and business-friendly neoliberals in the center and on the right.

The second big constraint is the fact that many sociocultural (semi-)professionals, especially those who are willing to vote for left-wing candidates and build organizations like DSA, also tend to be concentrated in the bigger metropolitan areas. The geographical concentration of the new left’s main social base is a problem because, as political scientist Jonathan Rodden illustrates in his excellent book Why Cities Lose, the US political system makes it difficult for voters who are spatially concentrated to transform their votes into proportional number of legislative seats. The relatively small, winner-take-all, single-member districts we use to elect most legislators in this country gives a systematic advantage to the party whose supporters are more evenly distributed in space, and right now that tends to be the Republicans.

One way of dealing with this problem is to fight for electoral reform, which would be quite difficult but perhaps not impossible in the roughly half of states that allow for citizen-led statewide ballot initiatives (the road is much more forbidding in the states that don’t). Another way is to make inroads among voters in small-town and rural places that are more likely to be receptive to a left-wing political agenda, namely younger people, Native Americans (particularly in the Plains states and interior West), immigrant workers, and public sector employees. Left-wing majorities are not on the near-term or even intermediate-term agenda in most of these places. But it should be possible to at least partially offset the GOP advantage there, and that is very important for shaping the outcomes of statewide and presidential elections in particular.

Great analysis, very clarifying

Jacobin couldn't publish this piece because it has intellectual merit and isn't a boring polemic simplistically repeating "democrats don't talk about 'class' enough" for the ten thousandth time. I read Karp's two pieces as well. Frustrating to read because doing polemics to defend a stale point instead of moving the conversation along. Hard to get through because that point is boring and belongs in the initial draft of analysis after Trump's 2016 win. I say this as a person who used to be obsessed with Jacobin.

Tell me about maintenance, roads, bridges, infrastructure, home repair and upkeep, sanitation, and the people who scrub your office floor. The country is falling apart, physically as well as intellectually. There's a lot of dirty work needs to be done. A lot of green to be made in the green new deal. And tech is people pulling cable, installing and repairing hardware: skilled physical labor isn't white collar unless you're repairing an animal.

"In other words, however you slice it, the essential trade-off comes down to the same constituencies Chuck Schumer called out in his famous dictum: 'For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia.'”

It amused me no end that Karp has "Brooklyn" in his twitter handle, eliding the fact that it's a marker of gentrification, the end of blue collar borough, just as "Jacobin" is. Nostalgic suburbanites cosplaying 18th century revolutionaries. Cut off any heads yet? "Jacobin" and the absurdly named "Brooklyn Institute", founded by immigrant South Asians with nostalgia for the Jewish NY Intellectuals. Add Phong Bui of The Brooklyn Rail". The Partisan Review crowd who were born working class and moved to Manhattan. But now it's Manhattanites moving out. And that's what you're called. "Do you think the Manhattanites will take over? I hope not. I like the diversity." That's a quote from 20 years ago in Queens. The Dimes Square crew are honest at least. Underpaid novice priests are not the working class. The working class has contempt for the downwardly mobile middle class. They're returning the contempt directed at them their entire lives. And now college students have to take "adulting classes" to learn how to live on their own. https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2019/12/09/how-to-be-an-adult

Johnny Goes to College

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/25/opinion/sunday/johnny-goes-to-college.html

---We head back to the dorm. Double-parking, we step out of the car, and Johnny hugs and kisses his dad, then embraces me in a strong, strapping-young-man hug, burying his head in my neck; this is the exact position we found ourselves in while I walked the floors with him in my arms during his colicky phase, and as he did then, he is crying into my neck.

This shocks me. I haven’t seen him cry like this since I told him that his father and I were separating. I had imagined I might say, “Ta ta for now,” Tigger’s optimistic sign-off, but I can manage only, “I love you, sweet baby.” Reeling back to the car after he walks into his new life, I turn to my ex and say, “That was a lot harder than I thought it would be.” I plant my forehead on the steering wheel. I sob.---

The biggest joke in that story is that the "Dad" is Paul Westerberg.